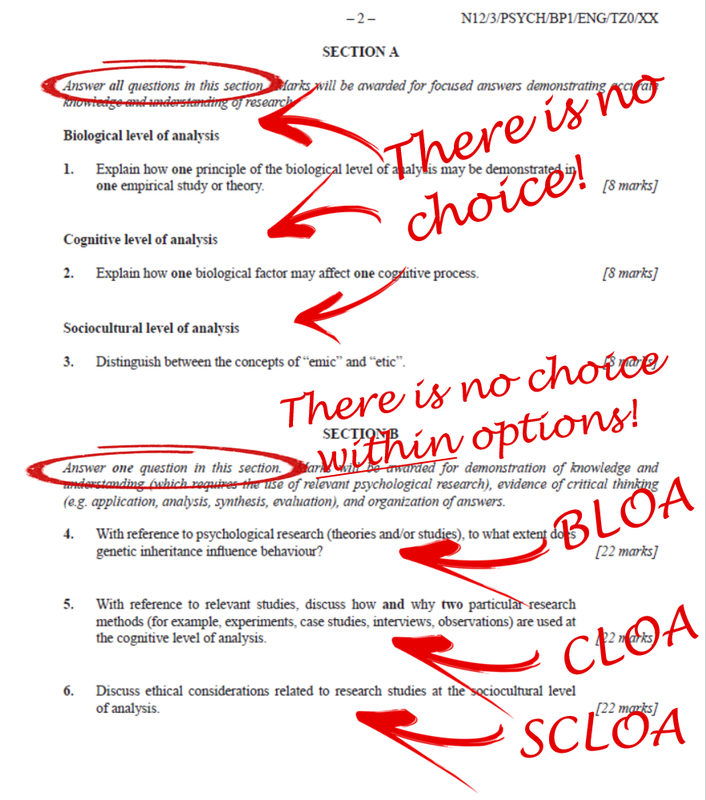

| IB Psychology students spot study then cross their fingers and hope, pray to interventionist gods, bribe teachers ($10,000 minimum, please!), and so on and such forth. Every IB Psychology student has been through this, every IB Psychology teacher has tried to stop his or her students going through this. Picture this, it’s the day of the first IB Psychology topic test of the year – the Cognitive Level of Analysis. Being a nice, kind IB Psychology teacher I have prepared a topic test which, very generously, allows the student a choice of answering one of three short answer questions (SAQs, 8 mark questions) and similarly, one of three extended response questions (ERQs, 22 mark questions). In the IB Psychology examination, there is no choice in the Paper 1 examination. Students file anxiously into the room, there is nervous chatter as they take their seats. I call for silence and distribute the test papers face down. I provide instructions and initiate the start of the test with my usual call to action … “Let’s rock and roll!”. What follows next is a very hard lesson to learn, but it is so much better to learn it at the start of the IB Psychology course, than in the mocks (where predicted grades are often confirmed) or even worse, the final examination. Every single IB student is time poor, there are competing demands from other subjects, TOK, extended essays, CAS requirements, sports, clubs and, of course, friends and just a little bit of a social life. Revision time always has an opportunity cost. I scan faces as my students turn their test papers over, in beautiful synchrony approximately one third of the class will raise their eyes skyward with a thankful little smile on their faces, another third will scrunch their eyes together and silently moan (perhaps a bolder one will bang her head on the desk – “Shhhh, silence!”), another third will take a deep breath, pause and dive in. One group has had their questions turn up, the other group hasn’t and the third group have studied all questions, but not memorised model answers. I could stop them right here, save | us all a lot of pain. The first group are the 7s, the second group will be very lucky to get 2s, and the third group are my 4s and 5s. Most IB Psychology students spot study. The good ones will learn the lesson early, the not-so-good ones will continue to ride their luck or hope their luck will finally turn. They all know the questions that will be asked (there are no surprises in the IB Psychology exams, see previous post) and will learn and memorise model answers to as many of these as they have time for. Your exams are upon you. Learn all of the model answers to one level of analysis (e.g., BLOA) in the Paper 1 exam and skip two at a maximum for each Paper 2 option (e.g., Abnormal and Human Relationships). Don’t be tempted to ride your luck or hope your luck will change – if the question you haven’t fully prepared for doesn't come up, you will completely wreck two years of hard (and interesting!) work … and, by the way, break your poor IB Psychology’s teacher’s heart in the process. Best of luck for your IB Psychology exams (although we all know we make our own luck). |

|

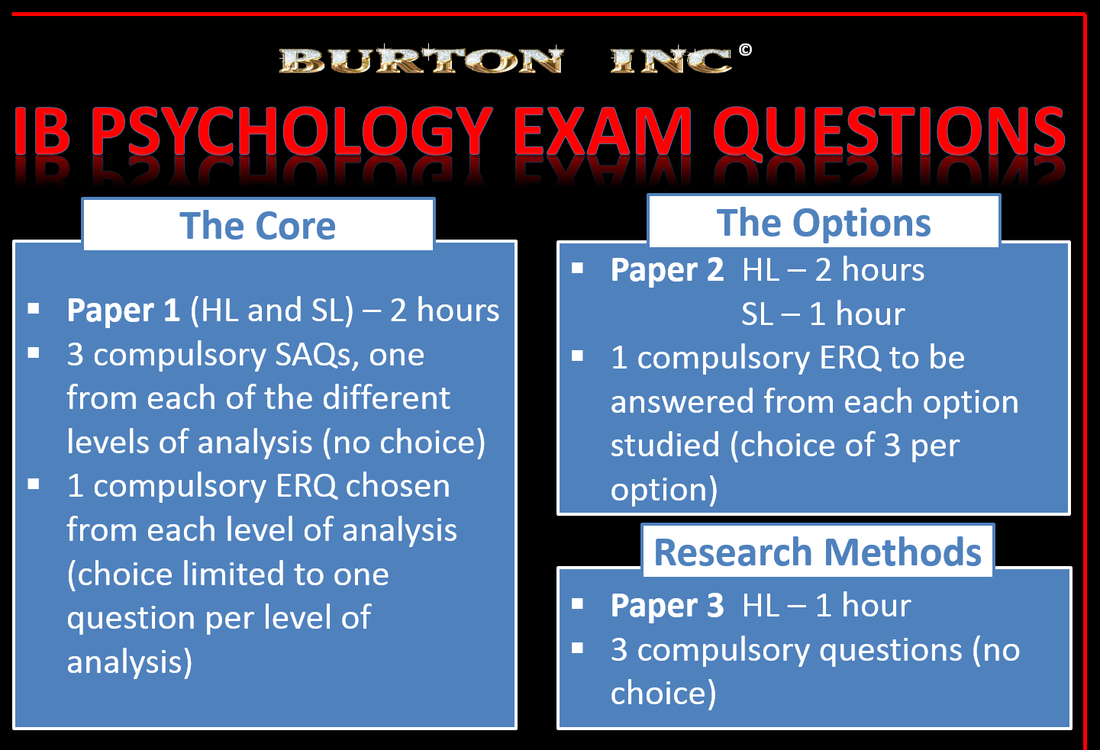

Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology Remember, we've taken the hard work out of your IB Psychology exams by preparing complete sets of model answers across both Paper 1 and Paper 2 exams. Your extended response answers will determine your final total mark The IB Psychology exams consist of either Extended Response Questions (ERQs) or Short Answer Questions (SAQs). An ERQ is a 22 mark question and an SAQ is an 8 mark question in Papers 1 and 2. HL Paper 3 questions are worth just 10 marks each, but students are still required to show good knowledge and critical thinking to achieve the full 10 marks here (see an earlier post about Paper 3 answers here). Your ability to write effective essay questions is tested to the limit in each of the three IB Psychology exams:

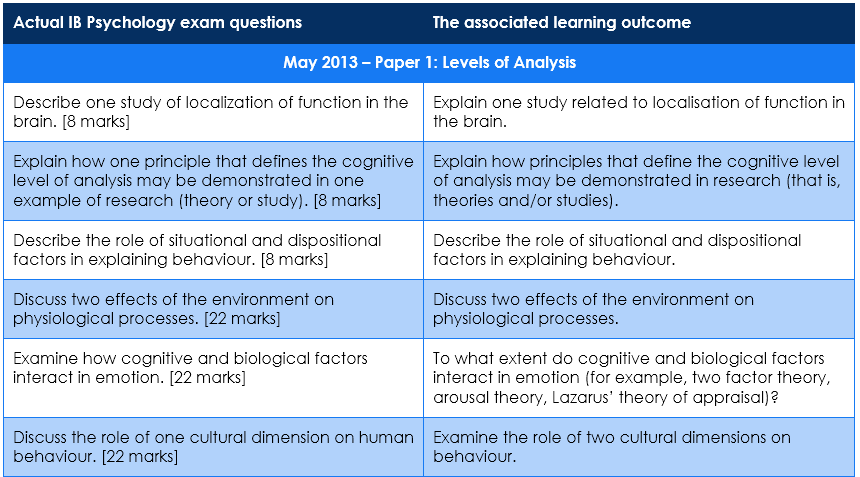

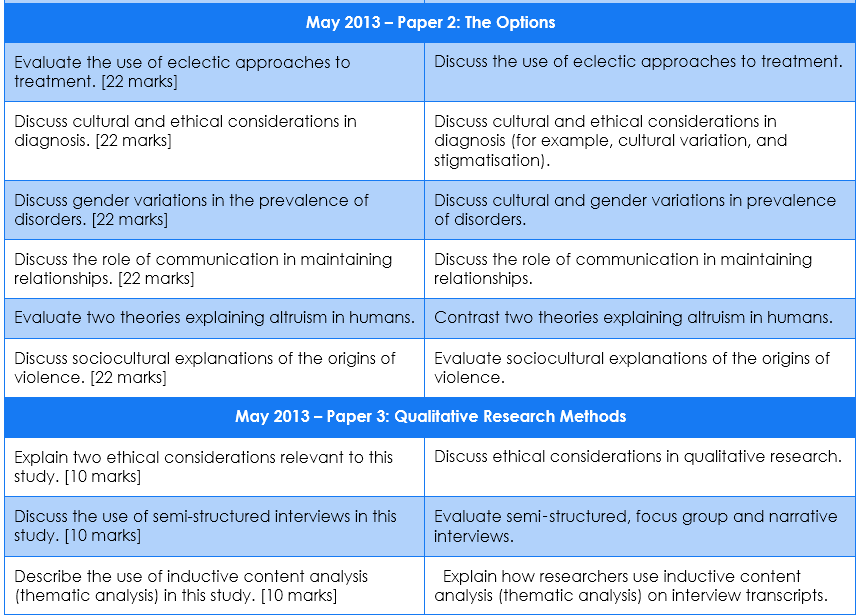

We have previously explained that there are no surprises in the IB Psychology examinations, you will know exactly the full range of ERQ questions that can be asked (see this previous post). An ERQ can never be based on a lower level learning outcome. For example the IB Psychology Sociocultural level of analysis has the learning outcome: "Explain 'emic' and 'etic' concepts." This will never be upgraded in the IB Psychology Paper 1 exam to a "Discuss 'emic' and 'etic' concepts" or "Evaluate research into 'emic' and 'etic' concepts". However, the SAQs can be derived from a higher order learning outcome. For example, in the Cognitive Level of Analysis we have the learning outcome: "Evaluate two models or theories of one cognitive process." Now this can be asked as an ERQ or downgraded to an SAQ by changing the command term. To make this an 8 mark SAQ the command term 'evaluate' can be substituted for 'explain' or 'analyse', for example. Now the SAQ may become: "Explain one model of a cognitive process." It is important that the student doesn't become too hung up on the three SAQs in the IB Psychology Paper 1 exam. The focus should always be on learning and practicing perfect model ERQs answers. If you they know the ERQ, the SAQ can easily be adapted. To illustrate this in action, consider the IB Psychology SCLOA learning outcome: "Discuss factors influencing conformity." An obvious candidate for an ERQ in the exam. Once the model ERQ has been learned and practiced then, come exam time, the student will be ready if this is needed to be approached in different ways for a compulsory SAQ. There are a few ways the examiners could set this question. We provide model answers for the three most likely scenarios. The key to full marks here is to know one study well and to be able to explain the three major social influence processes, which the student will be able to do if he or she has learned the model ERQ answer. Below we have three model SAQs based on the one higher order learning outcome follow; look for the different 'tweaks' based on the same information: 1. Explain one factor that influences conformity. Conformity can be defined as adjusting one's behaviour or thinking to match those of other people or a group standard. There are three major social influence processes which have been proposed to explain conformity, and these are informational influence, normative influence and referent informational influence. All of these explanations are, and some to a large extent, based on the influence of social norms. Social norms are group-held beliefs about how members should behave in a given context. Sociologists describe norms as informal understandings that govern society’s behaviours, while psychologists have adopted a more general definition, recognising smaller group units, like a team or an office, may also endorse norms separate or in addition to cultural or societal expectations, thus, group norms can be seen as a smaller subset of social norms. The psychological definition emphasises social norms' behavioural component, stating norms have two dimensions: how much behaviour is exhibited and how much the group approves of that behaviour. We are subjected to informational influence when we accept the views and attitudes of others as valid evidence about how things are in a particular situation. Having an accurate perception of reality is, of course, essential for our efficient functioning in our environment. Others are often viewed as valid sources of information, especially in situations where we cannot test the validity of our perceptions, beliefs and feelings. Informational influence seems to be the most likely explanation for Sherif’s (1935) research findings. He investigated the formation of group norms and conformity in an ambiguous situation (Sherif, 1935). This study relies on the autokinetic effect – an optical illusion that makes a stationary light appear to move when seen in complete darkness. Participants were led to believe that the experiment was investigating visual perception and told that the experimenter was going to move the light, something that was never done. The participants had to make 100 judgements as to how far the light, placed on the far wall of a darkened room, seemed to have moved. To start with, participants made their judgements alone. Their estimates fluctuated for some time before converging towards a standard estimate, a personal norm. Such personal norms varied considerably between participants. In further sessions of 100 trials on subsequent days, the participants were joined by two other participants. They took turns in a random order to call out their estimates of the light’s movements. In this group condition, participants’ estimates soon reflected the influence of estimates from the others in the group. Eventually a common group norm emerged, a social norm, which was the average of the individual estimates. Different groups formed different group norms. Interestingly, the participants denied that their estimates were influenced by the other group members. During a third phase of the study, participants performed the task alone again; their estimates showed a continued adherence to the social norm established during the group session. Here, because reality was ambiguous, participants used other people’s estimates as information to remove the ambiguity. Informational influence tends to produce genuine change in people’s beliefs thus leading to private conformity. Sherif’s work is important because it demonstrates how, at least in ambiguous settings, social norms can develop and become internalised (that is, function without the need of the actual presence of others). However, informational influence cannot be the only explanation for conformity, because conformity can be observed in situations where there is no ambiguity. 2. With reference to a study, explain conformity. Conformity can be defined as adjusting one's behaviour or thinking to match those of other people or a group standard. There are lots of reasons why people conform, including the desire/need to fit in or be accepted by others and maintaining order in one’s life. There are three major social influence processes which have been proposed to explain conformity, and these are informational influence, normative influence and referent informational influence. All of these explanations are, and some to a large extent, based on the influence of social norms. Social norms are group-held beliefs about how members should behave in a given context. We are subjected to informational influence when we accept the views and attitudes of others as valid evidence about how things are in a particular situation. Having an accurate perception of reality is, of course, essential for our efficient functioning in our environment. Others are often viewed as valid sources of information, especially in situations where we cannot test the validity of our perceptions, beliefs and feelings. Normative influence is another explanation of conformity. Normative influence underlies our conformity to the expectations of others. This type of influence is based on the need to be liked and accepted by others (the need to belong is one of the fundamental human motivations). In fear of social disapproval and rejection, we often behave in ways that conform to what others expect of us with little concern about the accuracy of beliefs we express or the soundness of our actions. SIT theorists have developed the referent informational influence hypothesis, and this forms the basis of SIT explanations of conformity. From an SIT perspective, conformity is not simply a matter of adhering to just any social norms; it is more likely to do with adhering to a person’s ingroup norms. We conform out of a sense of belongingness and by doing so we form and maintain desired social identities. It follows from this that we are far more likely to conform to the norms of groups we believe we belong to and identify with. Informational influence seems to be the most likely explanation for Sherif’s (1935) research findings. He investigated the formation of group norms and conformity in an ambiguous situation (Sherif, 1935). This study relies on the autokinetic effect – an optical illusion that makes a stationary light appear to move when seen in complete darkness. Participants were led to believe that the experiment was investigating visual perception and told that the experimenter was going to move the light, something that was never done. The participants had to make 100 judgements as to how far the light, placed on the far wall of a darkened room, seemed to have moved. To start with, participants made their judgements alone. Their estimates fluctuated for some time before converging towards a standard estimate, a personal norm. Such personal norms varied considerably between participants. In further sessions of 100 trials on subsequent days, the participants were joined by two other participants. They took turns in a random order to call out their estimates of the light’s movements. In this group condition, participants’ estimates soon reflected the influence of estimates from the others in the group. Eventually a common group norm emerged, a social norm, which was the average of the individual estimates. Different groups formed different group norms. Interestingly, the participants denied that their estimates were influenced by the other group members. During a third phase of the study, participants performed the task alone again; their estimates showed a continued adherence to the social norm established during the group session. 3. Explain the strengths and limitations of one study on conformity Informational influence seems to be the most likely explanation for Sherif’s (1935) research findings. He investigated the formation of group norms and conformity in an ambiguous situation (Sherif, 1935). This study relies on the autokinetic effect – an optical illusion that makes a stationary light appear to move when seen in complete darkness. Participants were led to believe that the experiment was investigating visual perception and told that the experimenter was going to move the light, something that was never done. The participants had to make 100 judgements as to how far the light, placed on the far wall of a darkened room, seemed to have moved. To start with, participants made their judgements alone. Their estimates fluctuated for some time before converging towards a standard estimate, a personal norm. Such personal norms varied considerably between participants. In further sessions of 100 trials on subsequent days, the participants were joined by two other participants. They took turns in a random order to call out their estimates of the light’s movements. In this group condition, participants’ estimates soon reflected the influence of estimates from the others in the group. Eventually a common group norm emerged, a social norm, which was the average of the individual estimates. Different groups formed different group norms. Interestingly, the participants denied that their estimates were influenced by the other group members. During a third phase of the study, participants performed the task alone again; their estimates showed a continued adherence to the social norm established during the group session. Here, because reality was ambiguous, participants used other people’s estimates as information to remove the ambiguity. Informational influence tends to produce genuine change in people’s beliefs thus leading to private conformity. Sherif’s work is important because it demonstrates how, at least in ambiguous settings, social norms can develop and become internalised (that is, function without the need of the actual presence of others). However, informational influence cannot be the only explanation for conformity, because conformity can be observed in situations where there is no ambiguity. The strengths of Sherif’s study include the fact that it was pioneering and still remains one of the most influential experiments in social psychology today. It has generated a large amount of research, especially in the role of group norms on conformity behaviour. The study clearly demonstrates how a group norm can be established and then continues to influence a person’s judgement even when the social influence of the group is no longer present. A minor limitation to this experiment surrounds the ethics of the deception involved. Participants were not informed about the purpose of the experiment (informed consent) but this was not the norm at the time of Sherif’s experiments, and the deception was arguably slight and necessary to avoid demand characteristics. Participants were debriefed at the end as to the true intents and purposes of the experiment. The major limitation is its lack of ecological validity. The task was artificial and ambiguous, and it is arguable that such ambiguous situations would never occur in real life situations. A possible counter argument to this criticism is that cognitive ‘anchoring’ can occur in our social groups. We have a tendency to use anchors or reference points to make decisions and evaluations, and sometimes these lead us astray. For example, if someone in my ingroup of girls informed me that 99% of teenage boys have body odour problems, then my perception of outgroup members on this domain will be influenced upwards towards this high initial anchor. Further, it turns out that we do not need the situation to be ambiguous for conformity to group norms to be observed. Of course, IB Psychology has taken all of the hard work out of your model answer preparation. We have the complete IB Psychology ERQ model answers, across both Paper 1 and Paper 2 exams, as well as the complete collection of model answers to the SAQ questions likely to be asked in the Paper 1 exam. We know you don't need reminding, but you should be well into your revision programme now. C'mon that IB Psychology 7! Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology 5 simple strategies for sure success in your IB Psychology course. Here, I am sharing with you the best five strategies I have for achieving that very, very elusive IB Psychology 7. Remember, just three per cent of all Higher Level IB Psychology students achieve the maximum mark of 7. TOP TIP ONE The IB Psychology Paper 1 examination has three sections - DO NO study for two of these! Choose one of either the IB Psychology Biological Level of Analysis, The Cognitive Level of Analysis or the Socio-Cultural Level of Analysis. Focus your study and preparation here and get really good at this one section. This section will bring you 30 marks out of a total 46. Our advice? Choose the IB Psychology Level of Analysis that your teacher begins with. This will maximise the amount of time you can spend learning this section. TOP TIP TWO Prepare and memorise model answers to ALL of the extended response questions. The extended response questions are the the IB Pychology examination essay questions - i.e., the big 22 mark answers. Prepare perfect 22 mark answers across one of the Levels of Analysis, and across each of the IB Psychology options (e.g., Abnormal and Human Relationships). In each option you will need to answer a single question. So for HL you will need to answer two 22 mark questions, one from each option. IN SL, just one 22 mark question from the single IB Psychology option you have studied. Aim for maximum marks here. So that's 44/44 or 22/22. TOP TIP THREE Aim for maximum marks in your IB Psychology IA. Essentially, any additional mark you gain in the internal assessment component of the course, is an additional total mark you can add to your final IB Psychology score. Start early. Put lots of effort in. Listen to your teacher. Ask your teacher to read over lots of sections before submitting the final draft. Get lots of feedback so your final draft is as good as most students' final submissions. TOP TIP FOUR Do NOT ignore the Qualitative Research Methods component of the course, because your IB Psychology teacher almost certainly WILL! It has long been identified that teachers neither spend enough time or go into this topic in enough depth. The majority of students do very poorly here, and as a result the grade boundaries in the HL Paper 3 examination are set incredibly low. Learn the content and learn to apply it to sample stimulus material. TOP TIP FIVE Forget about any of the short answer learning outcomes in the Options section of the IB Psychology course. Examiners can twist exam questions to fit these, but they usually don't. There are always straightforward back-up questions to fall back on. Save your time for memorising your model answers. Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology IB Psychology has a range of resources specifically dedicated to helping the IB Psychology student achieve maximum marks in the course. Find them all on our products page. It's not how much you write in the IB Psychology exams, it's what you write Students are always asking me how much they should be writing to answer a particular IB Psychology exam question. My response is always the same. Enough to meet the requirements of the particular IB Psychology command term (which I've covered in a previous post) and enough to provide sufficient information to answer the question ... but no more than that! Any unnecessary, extra time a student spends on one of their IB Psychology exam questions is time that she doesn't have to spend answering another examination question. And I have never met a student yet, in my long, long, long IB Psychology teaching career who has come out of an exam with that magical and elusive 7 saying that she had plenty of time to spare (therefore the exam paper doodling). To prove this point, take a look at two sample responses to short answer questions (SAQs) asked in past IB Psychology examinations (Paper 1, SL and HL). One response is an SAQ associated with the Cognitive Level of Analysis, the other, the Socio-Cultural Level of Analysis. You will see that full marks in SAQs can usually be gained with less than a page of writing, easily. The Cognitive Level of Analysis question: WITH REFERENCE TO ONE RESEARCH STUDY, EXPLAIN HOW ONE BIOLOGICAL FACTOR MAY AFFECT ONE COGNITIVE PROCESS Biological factors, such as hormones, can affect the cognitive process of memory. Hormones are chemical messengers secreted by cell or gland. These messengers are sent out from one part of the body to affect cells in other parts of the body. Hormones are often released directly into the bloodstream. One study done on this was by Newcomer. Newcomer wanted to test the role of glucocorticoids on memory. Glucocorticoids are chemicals that can stop inflammation. As Meany had found, exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids lead to a decrease in memory in rats and atrophy of the hippocampus. Newcomer wanted to see if this was also true in human beings. He wanted to test the effect of cortisol, a stress hormone secreted by the adrenal glands, on verbal declarative memory. The hippocampus plays the role of transferring declarative memories from STM to LTM. Cortisol appears to lead to hippocampal cell death. Newcomer ran a double-blind test in which participants either were given a high dose of cortisol (similar to a high level of stress), a low dose of cortisol or a placebo over a period of four days. The participants were asked to read a piece of prose. After the four days, they were asked to recall the data from the prose. Newcomer found that those who had been given high levels of cortisol had the worst recall of the text. When they stopped taking the pills, their memory levels returned to normal. Newcomer concluded that cortisol has a negative effect on the transfer and retrieval of STM to LTM. The Socio-Cultural Level of Analysis question: DESCRIBE ONE THEORY OF HOW STEREOTYPES ARE FORMED One theory that explains how stereotypes are formed is through either experience or society and then confirmation bias. Stereotypes are schema that people have of other people. These usually form from experiencing a certain event multiple times or from what society tells you to think. One study on the formation of stereotypes was done by Rogers & Frantz. They aimed to see if the amount of time that somebody was in Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) would affect their stereotypes of the locals. They studied European settlers in Rhodesia. They gave participants a test where multiple segregation and discrimination laws were listed, showing how much better the whites were treated in Rhodesia than the blacks. They then asked them how much they wanted things to either stay the same or change. The results were that the longer somebody had lived in Rhodesia, the less they wanted things to change and the more they liked the status quo. This shows that the longer someone had been living there, the higher amount of the stereotypes he had towards the locals. Those that wanted the change the most were the ones that had been there the least amount of time. This indicates that stereotypes form over time. When new European settlers came to Rhodesia they had no idea what to think and had no stereotypes toward the Africans. Because of this, they looked to others to see what to think. This is called informational social influence. They conformed to the ideas and stereotypes already existing in the White European community. They did this in order to connect to their “in-group.” Once learning these stereotypes, they then experience confirmation bias. This is when they only see and remember things that fit into the stereotype or schema that they now had of the locals and ignored the things that went against these stereotypes. This is how their stereotypes got stronger. One theory of the formation of stereotypes is that people look to others they consider their in-group to see what to think. Then through confirmation bias these stereotypes increase in intensity. The more time the Europeans had been in Rhodesia, the more they felt ok with discrimination against the locals and the stronger their stereotypes were. Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology Maximum marks in the diabolical IB Psychology HL Qualitative Research Methods

Describe the use of inductive content analysis (thematic analysis) in this study. [10 marks] Inductive content analysis is a measure of analysing data in a qualitative study. It involves the grounded theory – transferring a low order theme to a high order theme and IPA (Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis). The data collection is the first step which is done by semi-structured interview in this stimulus material. The data from the interview was “recorded” in the stimulus material which is then transcribed either by verbatim or postmodern transcription. Recorder themes are identified by transcription and then a step-by-step analysis is done to classify different sub-themes. The reading and re-reading of the data transcription several emergent themes are extracted which are then classified into different themes. These different sub-themes are analysed critically and further categorised into higher order themes. This categorisation process is evident in the stimulus material – “the content analysis showed that participant’s motivation could be categorised into four major or higher-order themes”. The stimulus material provides a detailed description of the four higher-order themes such as excitement and entertainment, emotional coping, and escaping from reality and interpersonal and social needs. These higher-order themes are then produced as a summary table after no more themes can be identified. This summary table is the produced account which is used for deriving the conclusion. As in the stimulus material “the researchers concluded that online gaming had the potential to be addictive.” Each step of the inductive content analysis requires credibility checks. For example, credibility checks by other researchers, coding, and reflexivity. These credibility checks appear on the margins and finally produce an account of the participants view rather than the researchers, thereby making the study trustworthy. Though the stimulus material did not present any kind of credibility checks employed by the researches, there is evidence of four higher-order themes makes the conclusions reliable as the study measures what it is expected to (psychological motivation to participate in online games).

Some nasty little surprises lying in wait to hook the unwary  Another IB Psychology student caught by surprise Another IB Psychology student caught by surprise Imagine writing what you think is the perfect response to a short answer question in your IB Psychology examination only to have a single sentence of your answer penalise you 50 per cent of the marks on offer. There are some very odd requirements that IB Psychology examiners must follow, and this can be infuriating for inexperienced IB Psychology teachers and unwary students. A frequently posed exam question relates to the principles that govern each of the three levels of analysis: The Biological, Cognitive and Socio-Cultural levels of analysis. There are always three different principles that govern each of these levels of analysis. For example, in the Biological Level of Analysis the three principles are: (i) there are biological correlates of behaviour, (ii) animal research can provide insight into human behaviour, and (iii) human behaviour is, to some extent, genetically based. The exam question that is often asked will ask you to outline, describe or explain one or two of these principles (e.g., Outline two principles that govern the Biological Level of Analysis.). Now students being students, and human nature being human nature, we have a need to show our examiners how intelligent we are; exams are our time to showcase the knowledge we have accumulated over the last two years. So we begin our short answer responses ... "There are three principles that govern the Biological Level of Analysis, and these are (i) there are biological correlates of behaviour, (ii) animal research can provide insight into human behaviour, and (iii) human behaviour is, to some extent, genetically based. ... " before going on to outline the second and third of these stated principles. Here the examiner face palms herself. Literally. The IB Psychology examination board has decided in their infinite wisdom that the first two principles that are mentioned in a student responses are the ones they have to be graded on. Thus the student picks up zero marks for the first principle because she hasn't outlined it, and zero marks for the third principle as the examiners consider it superfluous - the examiner has to focus on the first two principles mentioned in the response. A response worthy of the full 8 marks gets hammered down to a 3 or a 4. Yes, very, very pedantic! Below, we present a model short answer question (SAQ) response that will be awarded the full 8 marks. IB Psychology: The Biological Level of analysis A model short answer question (SAQ) response to the examination question: Outline principles that define the biological level of analysis. SAQ: Outline principles that define the biological level of analysis Biological psychology is a branch or type of psychology that brings together biology and psychology to understand behaviour and thought. Biological psychology looks at the link between biology and psychological events such as how information travels throughout our bodies (neural impulses, axons, dendrites, etc.), how different neurotransmitters effect behaviours. There are three principles that define the biological level of analysis which will each be covered, in turn. Principle 1: There are biological correlates of behaviour. This means that there are physiological origins of behaviour such as neurotransmitters, hormones, specialised brain areas, and genes. The biological level of analysis is based on reductionism, which is the attempt to explain complex behaviour in terms of simple causes. Principle 1 demonstrated in: Newcomer et al. (1999) performed an experiment on the role of the stress hormone cortisol on verbal declarative memory. Group 1 (high dose cortisol) had tablets containing 160 mg of cortisol for four days. Group 2 (low dose cortisol) had tablets with 40 mg of cortisol for four days. Group 3 (control) had placebo tablets. Participants listened to a prose paragraph and had to recall it as a test of verbal declarative memory. This memory system is often negatively affected by the increased level of cortisol under long-term stress. The results showed that group 1 showed the worst performance on the memory test compared to group 2 and 3. The experiment shows that an increase in cortisol over a period has a negative effect on memory. Principle 2: Animal research can provide insight into human behaviour. This means that researchers use animals to study physiological processes because it is assumed that most biological processes in non-human animals are the same as in humans. One important reason for using animals is that there is a lot of research where humans cannot be used for ethical reasons. Principle 2 demonstrated in: Rosenzweig and Bennet (1972) performed an experiment to study the role of environmental factors on brain plasticity using rats as participants. Group 1 was placed in an enriched environment with lots of toys. Group 2 was placed in a deprived environment with no toys. The rats spent 30 or 60 days in their respective environments before being killed. The brains of the rats in group 1 showed a thicker layer of neurons in the cortex compared to the deprived group. The study shows that the brain grows more neurons if stimulated. Principle 3: Human behaviour is, to some extent, genetically based. This means that behaviour can, to some extent, be explained by genetic inheritance, although this is rarely the full explanation since genetic inheritance should be seen as genetic predisposition which can be affected by environmental factors.

Principle 3 demonstrated in: Bouchard et al. (1990) performed the Minnesota twin study, a longitudinal study investigating the relative role of genes in IQ. The participants were MZ reared apart (MZA) and MZ reared together (MZT). The researchers found that MZT had a concordance rate of IQ of 86% compared to MZA with a concordance rate of IQ of 76%. This shows a link between genetic inheritance and intelligence but it does not rule out the role of the environment. Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology Another ERQ model answer from IB Psychology Abnormal psychology is based upon the assumption that we know what 'abnormal' is, which in turn, is based upon us knowing what 'normal' is. So, how exactly do we make these judgments? You're hanging out a LOT in your dark, smelly and incredibly messy bedroom, not talking to family and only interacting with your friends online. Teachers are concerned about you, your family is worried sick. Do you have some sort of social anxiety disorder? Surely this is a manifestation of a mental illness? ... but hang on! Isn't this just 'normal' teenage behaviour? Have you ever wondered just how easily you could be confined to a mental hospital if say, your parents, didn't like the way you were behaving? If their concepts of normality and abnormality differed from yours? The answer is, probably pretty easily, but not as easily as in the past, and more easily in some countries than in others. Thus, we need some some sort of objective definition or classification of what abnormal behaviour actually is, and how we can make a judgement as to whether someone has a mental illness or not. The IB Psychology learning outcome: Examine concepts of normality and abnormality, takes a very good look at this thought-provoking issue. Much of what we examine in the model ERQ answer focuses on Rosenhan's seminal research. Rosenhan (1973) performed some ground-breaking research with his quasi-experimental study. Here, he and his fellow researchers managed to gain admittance to a variety of psychiatric hospitals around the US after presenting themselves and claiming that a voice in their head was saying "empty", "hollow" and "thud". They found that getting committed was very easy, and getting out was very, very hard ... short videos examining concepts of mental illness and abnormality

Examine concepts of normality and abnormality Another exemplar model ERQ answer for the IB Psychology course. This one is from the Abnormal option and if the student manages to replicate in their IB Psychology exams they are guaranteed to be awarded the full possible 22/22 marks.  Examine concepts of normality and abnormality The presence of a mental disorder may be considered a deviation from mental health norms and hence the study of mental disorders is often known as abnormal psychology. ‘Normal’ and ‘abnormal’, as applied to human behaviour, are relative terms. Many people use these classifications subjectively and carelessly, often in a judgmental manner, to suggest good or bad behaviour. As defined in the dictionary, their accurate use would seem easy enough: ‘normal’ – conforming to a typical pattern and ‘abnormal’ – deviating from a norm. The trouble lies in the word norm. Whose norm? For what age person? At what period of history? In which culture? The definition of the word abnormal is simple enough but applying this to psychology poses a complex problem. The concept of abnormality is imprecise and difficult to define. Examples of abnormality can take many different forms and involve different features, so that, what at first sight seem quite reasonable definitions, turns out to be quite problematical. There are several different ways in which it is possible to define ‘abnormal’ as opposed to our ideas of what is ‘normal’ Defining normality Mental health model of normality (Jahoda, 1958) The model suggests criteria for what might constitute normal psychological health (in contrast to abnormal psychological health). Deviation from these criteria would mean that the health of an individual is ‘abnormal’:

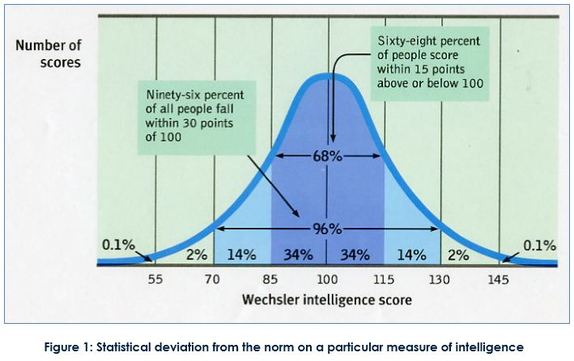

Evaluation of the mental health model of normality The majority of people would be categorised as ‘abnormal’ if the criteria were applied to them. It is relatively easy to establish criteria for what constitutes ‘physical health’ but it is impossible to establish and agree on what constitutes ‘psychological health’. According to Szasz (1962) psychological normality and abnormality are culturally defined concepts, which are not based on objective criteria. Taylor & Brown (1988) argue that the view that a psychologically healthy person is one that maintains close contact with reality is not in line with research findings. People generally have positive ‘illusions’ about themselves and they rate themselves more positively than others (Lewinshohn et al., 1980). For example most people rate themselves as being above average in driving ability, and above average in physical appearance, both of which are a statistical nonsense when considering the essential nature of an average. Further, the criteria in the model are culturally biased value judgements; i.e., they reflect an idealised perception of what it means to be human in a Western culture. For example, self-actualisation (Maslow, 1968) means the achievement of one's full potential through creativity, independence, spontaneity, and a grasp of the real world. The concept of self-actualisation to a South Sudanese in the middle of sectarian strife, war and famine would be nonsensical at that point in time. Defining abnormality The mental illness criterion (the medical model) The mental illness criterion sees psychological disorders (abnormality) as psychopathology. Pathology means ‘illness’ so it literally means ‘illness in the psyche’. The criterion is linked to psychiatry, which is a branch of medicine, specifically, a branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental and emotional disorders. Patients with psychological problems are seen as ‘ill’ in the same way as those who suffer from physiological illnesses. Diagnosis of mental illness is based on the clinician’s (clinical psychologist, psychiatrist) observations, the patient’s self-reports and diagnostic manuals (classification systems) that classify symptoms of specific disorders to help doctors find a correct diagnosis. The most widely used classification system is the new DSM-5, which is the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In the United States the DSM serves as a universal authority for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. Treatment recommendations, as well as payment by health care providers, are often determined by DSM classifications. Being diagnosed or labelled as being abnormal – mentally ill can have striking consequences in this model, as a controversial study designed to test the medical model and its conception of normality and abnormality. Rosenhahn (1973) – on being sane in insane places Aim: To test reliability and validity of diagnosis in a natural setting. Rosenhahn wanted to see if psychiatrists could distinguish between ‘abnormal’ and ‘normal’ behaviour. Procedure: This was a covert participant observation with eight participants consisting of five men and three women (including Rosenhahn himself). Their task was to follow the same instructions and present themselves at 12 psychiatric hospitals in the US. These pseudo-patients telephoned the hospital for an appointment, and arrived at the admissions office complaining that they had been hearing voices. They said the voice, which was unfamiliar and the same sex as themselves, was often unclear but it said “empty”, “hollow”, “thud”. After they had been admitted to the psychiatric ward, the pseudo patients stopped simulating any symptoms of abnormality. The pseudo patients took part in ward activities, speaking to patients and staff as they might ordinarily. When asked how they were feeling by staff they said they were fine and no longer experienced symptoms. Each pseudo patient had been told they would have to get out by their own devices by convincing staff they were sane. Results and conclusion: All participants were admitted to various psychiatric wards and all but one were diagnosed with schizophrenia (the other diagnosis was for manic depression). All pseudo-patients behaved normally while they were hospitalised because they were told they would only get out if the staff perceived them to be well enough. The pseudo-patients took notes when they were hospitalised but this was interpreted as a symptom of their illness by the staff. It took between 7 and 52 days before the participants were released. They came out with a diagnosis (schizophrenia in remission) so they were ‘labelled’. A follow-up study was done later where the staff at a specific psychiatric hospital were told that imposters would present themselves at the hospital and that they should try to rate each patient whether he or she was an imposter. Of the 193 patients, 41 were clearly identified as impostors by at least one member of the staff, 23 were suspected to be impostors by one psychiatrist, and 19 were suspected by one psychiatrist and one staff member. There were no impostors. Rosenhahn claims that the study demonstrates that psychiatrists cannot reliably tell the difference between people who are sane and those who are insane. The main experiment illustrated a failure to detect sanity, and the secondary study demonstrated a failure to detect insanity. Rosenhahn explains that psychiatric labels tend to stick in a way that medical labels do not and that everything a patient does is interpreted in accordance with the diagnostic label once it has been applied. Evaluation: This controversial study was conducted nearly 40 years ago but it had an enormous impact on psychiatry. It sparked off a discussion and revision of diagnostic procedures as well as discussion of the consequences of diagnosis for patients. The development of diagnostic manuals (e.g., DSM-V) has increased the validity and reliability of diagnosis of what is abnormal or normal in terms of mental health, although diagnostic tools are not without flaws. The method used raises ethical issues (the staff were not told about the research) but it was justified since the results provided evidence of problems in the diagnosis of mental illness (i.e., being non-beneficially abnormal) which could benefit others. There were serious ethical issues with the follow-up study since the staff thought that imposters would present, but they were real patients and may not have had the treatment they needed. Evaluation of the mental illness criterion Proponents of the mental illness criterion argue that it is an advantage to be diagnosed as ‘sick’ because it shows that people are not responsible for their acts. For example, an individual who does not get out of bed because they have been diagnosed for depression; i.e., labelled as being ‘depressed’ and not because they are fatigued (a symptom). Although the origin of some mental disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) can be linked to physiological changes in the brain, most psychological disorders cannot. Also, critics of the mental illness criterion argue that there is a stigma (i.e., a mark of infamy or disgrace) associated with mental illness. Abnormality as statistical deviation from the norm Deviance in this criterion is related to the statistical average. The definition implies that statistically common behaviour can be classified as ‘normal’. Behaviour that is deviant from the norm is consequently ‘abnormal’. In the normal distribution curve most behaviour falls in the middle. A normal distribution curve is a theoretical frequency distribution for a set of variable data (e.g., scores on an IQ test), usually represented by a bell-shaped curve symmetrical about the mean. An individual with an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 150 is a deviation from the norm of 100. It is statistically rare but it is considered desirable to have high intelligence. Mental retardation seen as an abnormality in the other direction (sometimes defined as having an IQ below 70) but this is considered undesirable. Obesity is becoming statistically ‘normal’ but obesity is considered undesirable. Evaluation of the statistical criterion The use of statistical frequency and deviation from the statistical norm is not a reliable criterion to define abnormal behaviour since what is ‘abnormal’ in a statistical sense may both be desirable and undesirable. What may be considered abnormal behaviour can differ from one culture to another so it is therefore impossible to establish universal standards for statistical abnormality. The model of statistical deviation from the norm always relates to a specific culture. Abnormality as deviation from social norms Social norms constitute informal or formal rules of how individuals are expected to behave. Deviant behaviour is behaviour that is considered undesirable or anti-social by the majority of people in a given society. Individuals who break rules of conduct or do not behave like the majority are defined as ‘abnormal’ according to this criterion. Social, cultural and historical factors may play a role in what is seen as ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’ within a certain society. For example, around the 1900s in the UK, homosexuality was seen as abnormal and people could be imprisoned or forcibly treated for this ‘mental illness’. Homosexuality was classified as an abnormal sexual deviation in the DSM-II (1968). In later revisions of the manual, homosexuality in itself was not seen as abnormal – only feeling distressed about it was. Evaluation of the deviation from statistical norms criterion This criterion is not objective or stable since it is related to socially based definitions that change across time and culture. Further, because the norm is based on morals and attitudes it is vulnerable to abuse. For example, political dissidents could be considered ‘abnormal’ and sent to hospitals for treatment, which was something that occurred in the former Soviet Union. Using this criterion could lead to discrimination against minorities, including people who suffer from psychological disorders. Psychological disorders may be defined and diagnosed in different ways across cultures and what seems to be a psychological disorder in one culture may not be seen the same way in another culture. The DSM includes disorders called ‘culture-bound syndromes’; for example, penis panic (!) or Koro. This indicates that it is impossible to set universal standards for classifying a behaviour as abnormal. General conclusion None of the above definitions provide a complete definition of abnormality. Mental health (e.g., Jahoda) and mental illness (i.e., the medical model) are probably two-sides of the same coin, but do provide insights of their own. Examining these concepts through statistical deviations from norms does not tell us about the desirability of the deviation. Attempting to define abnormality is in itself a culturally specific task. What seems abnormal in one culture may be seen as perfectly normal in another, and hence it is difficult to define abnormality. Word count: 2 000 Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology

The IB Psychology Exam Questions are the Learning Outcomes

|

IB DipLOMA PsychologY:The IB Psychology Blog. A place to share research and teaching and learning ideas for those studying and teaching Psychology for the IB Diploma Programme. Archives

April 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed