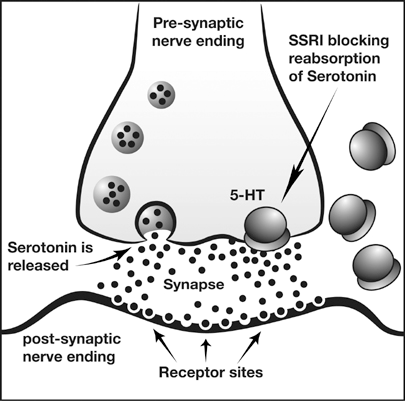

| Describe one interaction between cognition and physiology in terms of behaviour. The example used comes from the IB Psychology Abnormal option with regard to anxiety disorders. The sample SAQ should be awarded full marks. However, remember that Paper 2 IB Psychology examination questions will never be asked as SAQs, you only answer one 22 mark ERQ. One way in which cognition and physiology interact in behaviour has been seen in studies of panic attacks. Clark (1996) argues that panic attacks are the result of a catastrophic misinterpretation of stimuli. When there is an environmental stimulus - for example, a loud noise - the heart may begin to beat faster in response. This is a result of the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, preparing the body for possible fight or flight. When the heart begins to beat faster, the person may then begin to think "why is my heart beating faster?" Clark's theory is that people whose schema interpret bodily changes as dangerous or "scary," will begin to interpret the increase in heart-rate negatively. This then leads to a further increase in heart-rate, which then increases the concern. This is a positive feedback loop. The physiology affects the cognition and the cognition affects the physiology, resulting in a panic attack. | Telch & Harrington (1992) did a study with a group of university students. Each student was given a written test to see their level of anxiety with regard to health and wellness. All participants took part in two trials. In the first trial, they were asked to breathe room air. In the second trial, they were asked to breathe air with high levels of CO2. The participants were told that the air would make them feel relaxed. In the "room air" group, no one felt aroused, in spite of their score on the anxiety test. However, when asked to breathe in CO2, in the low anxiety group 5% experienced high arousal whereas 52% of the high anxiety group did. In other words, it was the interaction of high anxiety schema and physiological responses to stimuli that lead to the panic response. panic attack! - It's not prettyAuthor: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology |

Are America's children over-medicated?

Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology Another ERQ model answer from IB Psychology Abnormal psychology is based upon the assumption that we know what 'abnormal' is, which in turn, is based upon us knowing what 'normal' is. So, how exactly do we make these judgments? You're hanging out a LOT in your dark, smelly and incredibly messy bedroom, not talking to family and only interacting with your friends online. Teachers are concerned about you, your family is worried sick. Do you have some sort of social anxiety disorder? Surely this is a manifestation of a mental illness? ... but hang on! Isn't this just 'normal' teenage behaviour? Have you ever wondered just how easily you could be confined to a mental hospital if say, your parents, didn't like the way you were behaving? If their concepts of normality and abnormality differed from yours? The answer is, probably pretty easily, but not as easily as in the past, and more easily in some countries than in others. Thus, we need some some sort of objective definition or classification of what abnormal behaviour actually is, and how we can make a judgement as to whether someone has a mental illness or not. The IB Psychology learning outcome: Examine concepts of normality and abnormality, takes a very good look at this thought-provoking issue. Much of what we examine in the model ERQ answer focuses on Rosenhan's seminal research. Rosenhan (1973) performed some ground-breaking research with his quasi-experimental study. Here, he and his fellow researchers managed to gain admittance to a variety of psychiatric hospitals around the US after presenting themselves and claiming that a voice in their head was saying "empty", "hollow" and "thud". They found that getting committed was very easy, and getting out was very, very hard ... short videos examining concepts of mental illness and abnormality

Examine concepts of normality and abnormality Another exemplar model ERQ answer for the IB Psychology course. This one is from the Abnormal option and if the student manages to replicate in their IB Psychology exams they are guaranteed to be awarded the full possible 22/22 marks.  Examine concepts of normality and abnormality The presence of a mental disorder may be considered a deviation from mental health norms and hence the study of mental disorders is often known as abnormal psychology. ‘Normal’ and ‘abnormal’, as applied to human behaviour, are relative terms. Many people use these classifications subjectively and carelessly, often in a judgmental manner, to suggest good or bad behaviour. As defined in the dictionary, their accurate use would seem easy enough: ‘normal’ – conforming to a typical pattern and ‘abnormal’ – deviating from a norm. The trouble lies in the word norm. Whose norm? For what age person? At what period of history? In which culture? The definition of the word abnormal is simple enough but applying this to psychology poses a complex problem. The concept of abnormality is imprecise and difficult to define. Examples of abnormality can take many different forms and involve different features, so that, what at first sight seem quite reasonable definitions, turns out to be quite problematical. There are several different ways in which it is possible to define ‘abnormal’ as opposed to our ideas of what is ‘normal’ Defining normality Mental health model of normality (Jahoda, 1958) The model suggests criteria for what might constitute normal psychological health (in contrast to abnormal psychological health). Deviation from these criteria would mean that the health of an individual is ‘abnormal’:

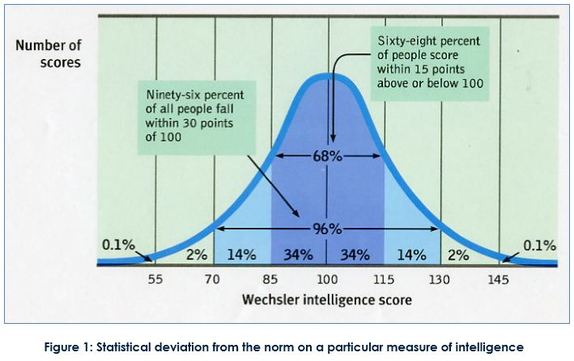

Evaluation of the mental health model of normality The majority of people would be categorised as ‘abnormal’ if the criteria were applied to them. It is relatively easy to establish criteria for what constitutes ‘physical health’ but it is impossible to establish and agree on what constitutes ‘psychological health’. According to Szasz (1962) psychological normality and abnormality are culturally defined concepts, which are not based on objective criteria. Taylor & Brown (1988) argue that the view that a psychologically healthy person is one that maintains close contact with reality is not in line with research findings. People generally have positive ‘illusions’ about themselves and they rate themselves more positively than others (Lewinshohn et al., 1980). For example most people rate themselves as being above average in driving ability, and above average in physical appearance, both of which are a statistical nonsense when considering the essential nature of an average. Further, the criteria in the model are culturally biased value judgements; i.e., they reflect an idealised perception of what it means to be human in a Western culture. For example, self-actualisation (Maslow, 1968) means the achievement of one's full potential through creativity, independence, spontaneity, and a grasp of the real world. The concept of self-actualisation to a South Sudanese in the middle of sectarian strife, war and famine would be nonsensical at that point in time. Defining abnormality The mental illness criterion (the medical model) The mental illness criterion sees psychological disorders (abnormality) as psychopathology. Pathology means ‘illness’ so it literally means ‘illness in the psyche’. The criterion is linked to psychiatry, which is a branch of medicine, specifically, a branch of medicine that deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mental and emotional disorders. Patients with psychological problems are seen as ‘ill’ in the same way as those who suffer from physiological illnesses. Diagnosis of mental illness is based on the clinician’s (clinical psychologist, psychiatrist) observations, the patient’s self-reports and diagnostic manuals (classification systems) that classify symptoms of specific disorders to help doctors find a correct diagnosis. The most widely used classification system is the new DSM-5, which is the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In the United States the DSM serves as a universal authority for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. Treatment recommendations, as well as payment by health care providers, are often determined by DSM classifications. Being diagnosed or labelled as being abnormal – mentally ill can have striking consequences in this model, as a controversial study designed to test the medical model and its conception of normality and abnormality. Rosenhahn (1973) – on being sane in insane places Aim: To test reliability and validity of diagnosis in a natural setting. Rosenhahn wanted to see if psychiatrists could distinguish between ‘abnormal’ and ‘normal’ behaviour. Procedure: This was a covert participant observation with eight participants consisting of five men and three women (including Rosenhahn himself). Their task was to follow the same instructions and present themselves at 12 psychiatric hospitals in the US. These pseudo-patients telephoned the hospital for an appointment, and arrived at the admissions office complaining that they had been hearing voices. They said the voice, which was unfamiliar and the same sex as themselves, was often unclear but it said “empty”, “hollow”, “thud”. After they had been admitted to the psychiatric ward, the pseudo patients stopped simulating any symptoms of abnormality. The pseudo patients took part in ward activities, speaking to patients and staff as they might ordinarily. When asked how they were feeling by staff they said they were fine and no longer experienced symptoms. Each pseudo patient had been told they would have to get out by their own devices by convincing staff they were sane. Results and conclusion: All participants were admitted to various psychiatric wards and all but one were diagnosed with schizophrenia (the other diagnosis was for manic depression). All pseudo-patients behaved normally while they were hospitalised because they were told they would only get out if the staff perceived them to be well enough. The pseudo-patients took notes when they were hospitalised but this was interpreted as a symptom of their illness by the staff. It took between 7 and 52 days before the participants were released. They came out with a diagnosis (schizophrenia in remission) so they were ‘labelled’. A follow-up study was done later where the staff at a specific psychiatric hospital were told that imposters would present themselves at the hospital and that they should try to rate each patient whether he or she was an imposter. Of the 193 patients, 41 were clearly identified as impostors by at least one member of the staff, 23 were suspected to be impostors by one psychiatrist, and 19 were suspected by one psychiatrist and one staff member. There were no impostors. Rosenhahn claims that the study demonstrates that psychiatrists cannot reliably tell the difference between people who are sane and those who are insane. The main experiment illustrated a failure to detect sanity, and the secondary study demonstrated a failure to detect insanity. Rosenhahn explains that psychiatric labels tend to stick in a way that medical labels do not and that everything a patient does is interpreted in accordance with the diagnostic label once it has been applied. Evaluation: This controversial study was conducted nearly 40 years ago but it had an enormous impact on psychiatry. It sparked off a discussion and revision of diagnostic procedures as well as discussion of the consequences of diagnosis for patients. The development of diagnostic manuals (e.g., DSM-V) has increased the validity and reliability of diagnosis of what is abnormal or normal in terms of mental health, although diagnostic tools are not without flaws. The method used raises ethical issues (the staff were not told about the research) but it was justified since the results provided evidence of problems in the diagnosis of mental illness (i.e., being non-beneficially abnormal) which could benefit others. There were serious ethical issues with the follow-up study since the staff thought that imposters would present, but they were real patients and may not have had the treatment they needed. Evaluation of the mental illness criterion Proponents of the mental illness criterion argue that it is an advantage to be diagnosed as ‘sick’ because it shows that people are not responsible for their acts. For example, an individual who does not get out of bed because they have been diagnosed for depression; i.e., labelled as being ‘depressed’ and not because they are fatigued (a symptom). Although the origin of some mental disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) can be linked to physiological changes in the brain, most psychological disorders cannot. Also, critics of the mental illness criterion argue that there is a stigma (i.e., a mark of infamy or disgrace) associated with mental illness. Abnormality as statistical deviation from the norm Deviance in this criterion is related to the statistical average. The definition implies that statistically common behaviour can be classified as ‘normal’. Behaviour that is deviant from the norm is consequently ‘abnormal’. In the normal distribution curve most behaviour falls in the middle. A normal distribution curve is a theoretical frequency distribution for a set of variable data (e.g., scores on an IQ test), usually represented by a bell-shaped curve symmetrical about the mean. An individual with an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 150 is a deviation from the norm of 100. It is statistically rare but it is considered desirable to have high intelligence. Mental retardation seen as an abnormality in the other direction (sometimes defined as having an IQ below 70) but this is considered undesirable. Obesity is becoming statistically ‘normal’ but obesity is considered undesirable. Evaluation of the statistical criterion The use of statistical frequency and deviation from the statistical norm is not a reliable criterion to define abnormal behaviour since what is ‘abnormal’ in a statistical sense may both be desirable and undesirable. What may be considered abnormal behaviour can differ from one culture to another so it is therefore impossible to establish universal standards for statistical abnormality. The model of statistical deviation from the norm always relates to a specific culture. Abnormality as deviation from social norms Social norms constitute informal or formal rules of how individuals are expected to behave. Deviant behaviour is behaviour that is considered undesirable or anti-social by the majority of people in a given society. Individuals who break rules of conduct or do not behave like the majority are defined as ‘abnormal’ according to this criterion. Social, cultural and historical factors may play a role in what is seen as ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’ within a certain society. For example, around the 1900s in the UK, homosexuality was seen as abnormal and people could be imprisoned or forcibly treated for this ‘mental illness’. Homosexuality was classified as an abnormal sexual deviation in the DSM-II (1968). In later revisions of the manual, homosexuality in itself was not seen as abnormal – only feeling distressed about it was. Evaluation of the deviation from statistical norms criterion This criterion is not objective or stable since it is related to socially based definitions that change across time and culture. Further, because the norm is based on morals and attitudes it is vulnerable to abuse. For example, political dissidents could be considered ‘abnormal’ and sent to hospitals for treatment, which was something that occurred in the former Soviet Union. Using this criterion could lead to discrimination against minorities, including people who suffer from psychological disorders. Psychological disorders may be defined and diagnosed in different ways across cultures and what seems to be a psychological disorder in one culture may not be seen the same way in another culture. The DSM includes disorders called ‘culture-bound syndromes’; for example, penis panic (!) or Koro. This indicates that it is impossible to set universal standards for classifying a behaviour as abnormal. General conclusion None of the above definitions provide a complete definition of abnormality. Mental health (e.g., Jahoda) and mental illness (i.e., the medical model) are probably two-sides of the same coin, but do provide insights of their own. Examining these concepts through statistical deviations from norms does not tell us about the desirability of the deviation. Attempting to define abnormality is in itself a culturally specific task. What seems abnormal in one culture may be seen as perfectly normal in another, and hence it is difficult to define abnormality. Word count: 2 000 Author: Derek Burton – Passionate about IB Psychology

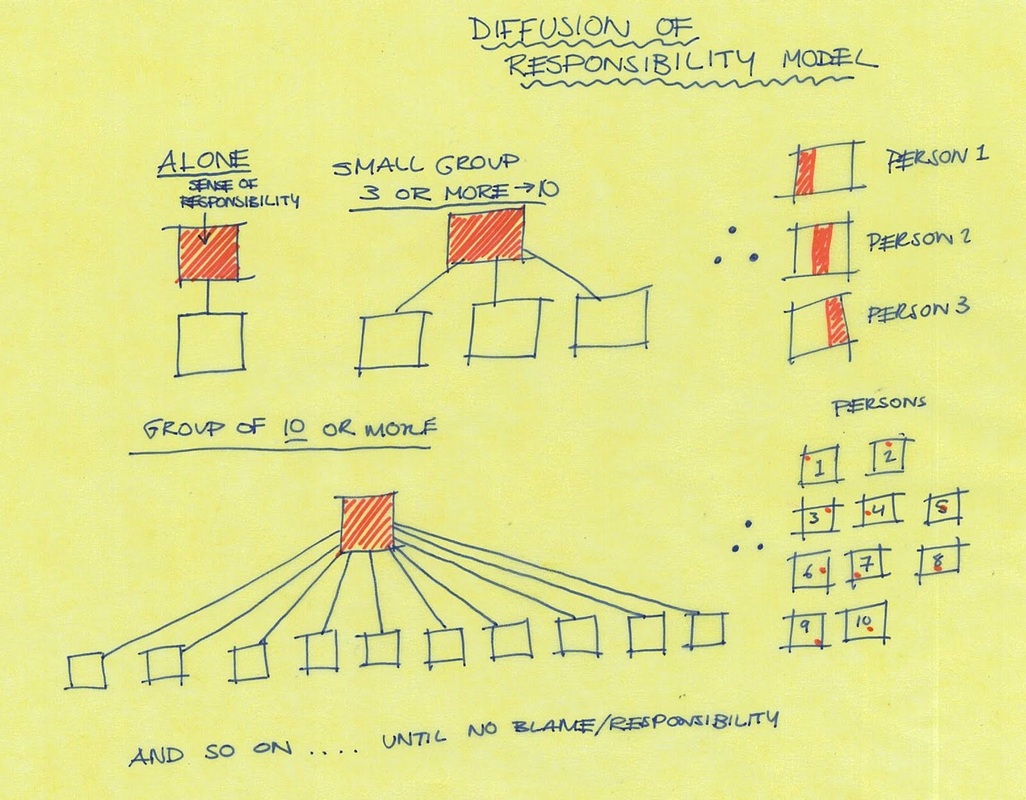

Examine factors influencing bystanderismBystanderism is the phenomenon of a person or people not intervening despite awareness of another person’s needs; i.e., an individual is less likely to help in an emergency situation when passive bystanders are present. It can cover a range of situations from being aware that a neighbour being physically abusive to his family but ignores it, walking past someone lying slumped on a pavement as the others preceding you have done, or ignoring the plight of a bullied child at school. The back ground for research on bystanderism was the Kitty Genovese murder in New York City in 1964. She was attacked, raped and stabbed several times over a period of 30 minutes by a psychopath. Later a large number of witnesses that they had heard screaming or seen a man attacking the woman (38 later testified as having heard her screams), yet none of them had intervened or called the police until it was too late. Afterwards they said that they did not want to become involved or thought that someone else would intervene. Researchers here established a cognitive model to explain the decision an individual makes to act or not. One of the key conclusions they drew was that the number of bystanders present has an enormous influence on the likelihood that one of them will help. This essay will address two theories regarding factors that influence bystanderism: the theory of the unresponsive bystander and the cost-reward model of helping, before examining the role of individual personality characteristics. Latane & Darley (1970) proposed the theory of the unresponsive bystander. According to the theory the presence of other people or just the perception that other people are witnessing the event will decrease the likelihood that an individual will intervene in an emergency due to such psychological processes like:

Latane & Darley (1968) suggested a cognitive decision model. They argue that helping requires the bystander to:

At each of these stages, the bystander can make a decision to help or not. Latane & Darley (1968) conducted an experiment to investigate bystander intervention and diffusion of responsibility. Aim: To investigate if the number of witnesses of an emergency influences people’s helping in an emergency situation. Procedure: As part of course credit, 72 students (59 female and 13 male) participated in the experiment. They were asked to discuss what kind of personal problems new college students could have in an urban area. Each participant sat alone in a booth with a pair of headphones and a microphone. They were told that the discussion took place via an intercom to protect the anonymity of participants. At one point in the experiment a participant (confederate) staged a seizure. The independent variable (IV) of the study was the number of persons (bystanders) that the participant thought listened to the same discussion. The dependent variable (DV) was the time it took for the participant to react from the start of the victim’s fit until the participant contacted the experimenter. Results and conclusion: The number of bystanders had a major effect on the participant’s reaction. Of the participants in the alone condition, 85% went out and reported the seizure. Only 31% reported the seizure when they believed there were four bystanders. The gender of the bystander did not make a difference. Ambiguity about a situation and thinking that other people might intervene (i.e., diffusion of responsibility) were factors that influenced bystanderism in this experiment. During debriefing students answered a questionnaire with various items to describe their reactions to the experiment, for example “I did not know what to do” (18 out of 65 students selected this) or “I did not know exactly what was happening” (26 out of 65) or “I thought it must be some kind of fake” (20 out of 65). Evaluation: There was participant bias (psychology students participating for course credits). Ecological validity is a concern due to the artificiality of the experimental situation (e.g., the laboratory situation and the fact that bystanders could only hear the victim and the other bystanders could add to the artificiality. Finally, there are ethical considerations in that participants were deceived and exposed to an anxiety-provoking situation. Another theory about factors affecting bystanderism was developed by Pilliavin et al. (1969). This is the cost reward model of helping, and the theory stipulates that both cognitive (cost-benefit analysis) and emotional factors (unpleasant emotional arousal) determine whether bystanders to an emergency will intervene. The model focuses on egoistic motivation to escape an unpleasant emotional state (opposite of altruistic motivation). Empathy evokes altruistic motivation to reduce another person’s distress whereas personal distress evokes an egoistic motivation to reduce one’s own distress, or recognition that helping will produce a reward (e.g., strong feeling of virtuousness or social approval). The theory was suggested based on a field experiment in New York’s subway. The subway Samaritan (Pilliavin, 1969) Aim: The aim of this field experiment was to investigate the effect of various variables on helping behaviour. Procedure:

Results and conclusion: The results showed that a person who appeared ill was more likely to receive help than one who appeared drunk. In 60% of the trials where the victim received help more than one person offered assistance. The researcher did not find support for diffusion of responsibility. They argue that this could be because the observers could clearly see the victim and decide whether or not there was an emergency situation. Pilliavin et al. found no strong relationship between the number of bystanders and the speed of helping, which is contrary to the theory of the unresponsive bystander. Evaluation: This study has higher ecological validity than laboratory experiments and it resulted in a theoretical explanation of factors influencing bystanderism. Based on this study the researchers suggested that the cost-reward model of helping involves observation of an emergency situation that leads to an emotional arousal and an interpretation of that arousal (e.g., empathy, disgust, fear) this serves as a motivation to either help of not, based on an evaluation of costs and rewards of helping:

Evaluation of the model: The model assumes that bystanders make a rational cost-benefit analysis rather than acting intuitively and on impulse. It also assumes that people only help for egoistic reasons, which is probably not true. Most of the research on bystanderism is conducted as laboratory or field experiments but findings have been applied to explain real-life situations. Another key point to consider when examining factors that influence bystanderism that neither the theory of the unresponsive bystander or the cost reward model of helping takes into consideration, is that there is significant individual variance that cannot be wholly attributable to the situation. Dispositional or personality characteristics are important in determining whether someone will help or not in an emergency situation. There is evidence that dispositional factors and personal norms are influential in determining the likelihood of bystanderism in an individual. Oliner & Oliner (1988) examined dispositional factors and personal norms in helping in an emergency situation, in this case, the Holocaust. The Holocaust was an exceptional life threatening emergency situation for the European Jews. Witnesses to the deportation of Jews all over Europe reacted in different ways. Some approved of the anti-Semitic policies, many were bystanders and a few risked their own life to save Jews. Within the context of the Second World War, saving Jews was a risky behaviour because it was illegal in many countries and the Jews were socially marginalised (pariahs). Despite this, some people decided to help (act altruistically). Heroic helpers such as those who saved Jews under the Holocaust (e.g., Oscar Schindler of ‘Schindler’s List fame) may have strong personal norms. Those that risk their lives to help others in situations like the Holocaust often deviate radically from the norms of their society. Oliner & Oliner (1988) examined the role of dispositional factors and personal norms in helping. These researchers interviewed 231 Europeans who had participated in saving Jews in Nazi Europe and 126 other similar people who did not rescue Jews. Of the rescuers, 67% had been asked to help, either by a victim or by someone else. One they had agreed to help they responded positively to subsequent requests. Results showed that rescuers shared personality characteristics and expressed greater pity or empathy compared to non-rescuers. Rescuers were more likely to be guided by personal norms (high ethical values, belief in equity, and perception of people as equal). Rescuers often said that parental behaviour had made an important contribution to the rescuer’s personal norms. For example, the parents of rescuers had few negative stereotypes of Jews compared to non-rescuers. The family of rescuers also tended to believe in the universal similarity of all people. Other factors such as similarity, victim attributes, responsibility, mood, competence and experience can also influence the degree of bystandersim in any person or emergency situation. These factors are not considered in the two models examined here, but have been shown to of some importance. General conclusion Both the theory of the unresponsive bystander and the cost-reward model of helping are cognitive models of decision making where individuals weigh up several factors regarding the emergency situation, consciously or unconsciously, before making their decision to help or not. Both of these models have good predictive power as to how people will behave in real life emergency situations; however each does have its own limitations. Neither of these models takes into account the influence of personality factors, which may be of considerable influence in bystanderism. Word count: 2 000

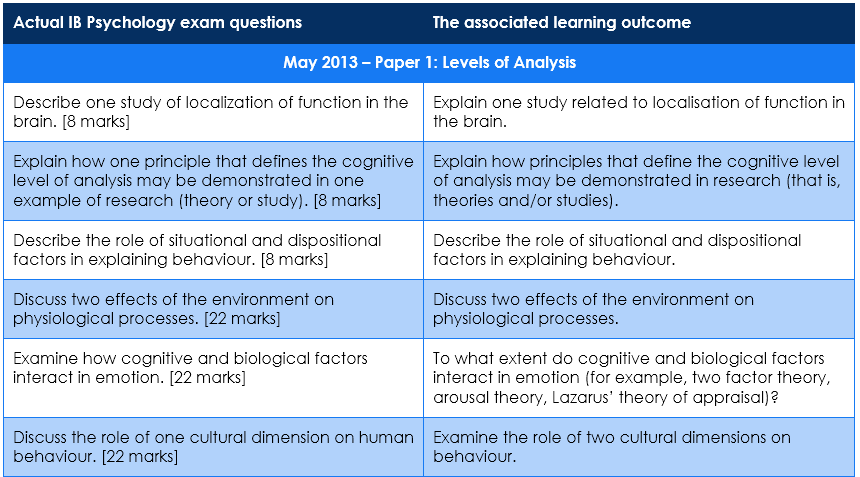

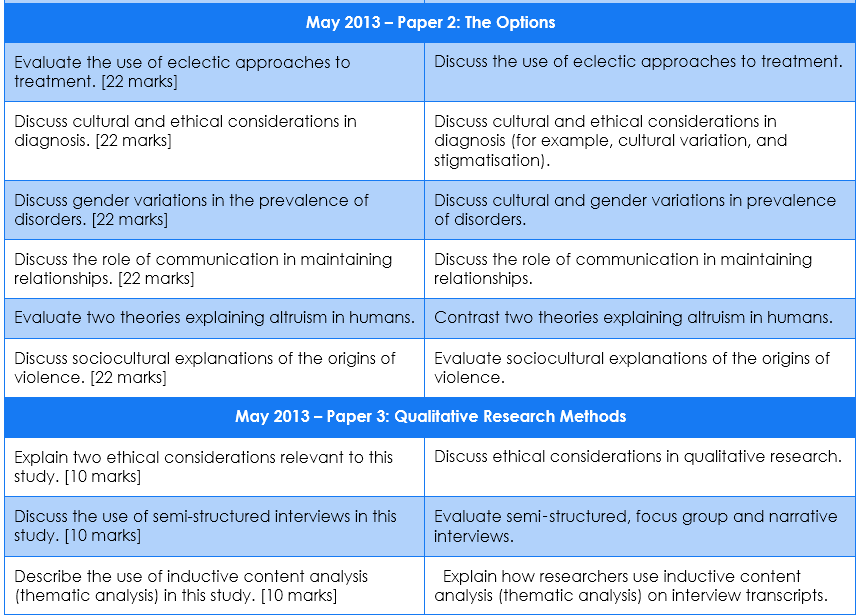

The IB Psychology Exam Questions are the Learning Outcomes

|

IB DipLOMA PsychologY:The IB Psychology Blog. A place to share research and teaching and learning ideas for those studying and teaching Psychology for the IB Diploma Programme. Archives

April 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed