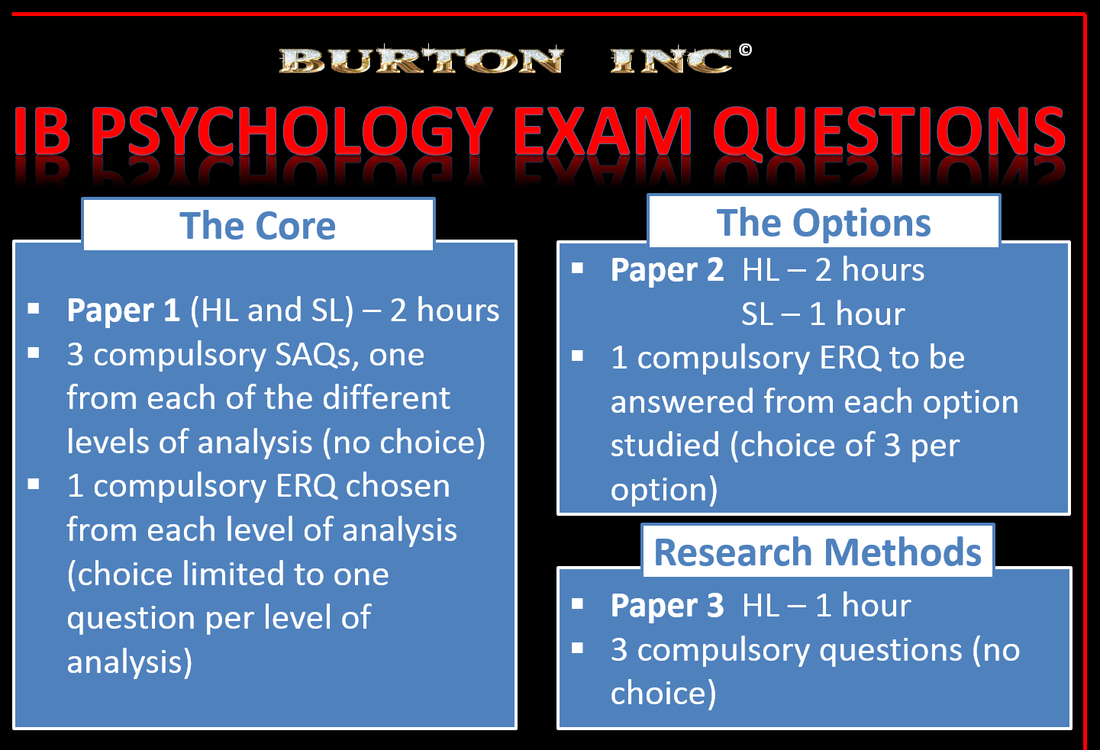

Your ability to write effective essay questions is tested to the limit in each of the three IB Psychology exams:

- Paper 1 requires you to answer one ERQ and three SAQs, thus half your marks are weighted on your sole essay answer.

- Paper 2 is only assessed through ERQs.

- Paper 3 are a messy hybrid, three SAQs that require you to show critical thinking as well as knowledge, thus, they are worth 10 marks each.

However, the SAQs can be derived from a higher order learning outcome. For example, in the Cognitive Level of Analysis we have the learning outcome: "Evaluate two models or theories of one cognitive process." Now this can be asked as an ERQ or downgraded to an SAQ by changing the command term. To make this an 8 mark SAQ the command term 'evaluate' can be substituted for 'explain' or 'analyse', for example. Now the SAQ may become: "Explain one model of a cognitive process."

It is important that the student doesn't become too hung up on the three SAQs in the IB Psychology Paper 1 exam. The focus should always be on learning and practicing perfect model ERQs answers. If you they know the ERQ, the SAQ can easily be adapted.

To illustrate this in action, consider the IB Psychology SCLOA learning outcome: "Discuss factors influencing conformity." An obvious candidate for an ERQ in the exam. Once the model ERQ has been learned and practiced then, come exam time, the student will be ready if this is needed to be approached in different ways for a compulsory SAQ. There are a few ways the examiners could set this question. We provide model answers for the three most likely scenarios. The key to full marks here is to know one study well and to be able to explain the three major social influence processes, which the student will be able to do if he or she has learned the model ERQ answer.

Below we have three model SAQs based on the one higher order learning outcome follow; look for the different 'tweaks' based on the same information:

Conformity can be defined as adjusting one's behaviour or thinking to match those of other people or a group standard. There are three major social influence processes which have been proposed to explain conformity, and these are informational influence, normative influence and referent informational influence. All of these explanations are, and some to a large extent, based on the influence of social norms. Social norms are group-held beliefs about how members should behave in a given context. Sociologists describe norms as informal understandings that govern society’s behaviours, while psychologists have adopted a more general definition, recognising smaller group units, like a team or an office, may also endorse norms separate or in addition to cultural or societal expectations, thus, group norms can be seen as a smaller subset of social norms. The psychological definition emphasises social norms' behavioural component, stating norms have two dimensions: how much behaviour is exhibited and how much the group approves of that behaviour.

We are subjected to informational influence when we accept the views and attitudes of others as valid evidence about how things are in a particular situation. Having an accurate perception of reality is, of course, essential for our efficient functioning in our environment. Others are often viewed as valid sources of information, especially in situations where we cannot test the validity of our perceptions, beliefs and feelings.

Informational influence seems to be the most likely explanation for Sherif’s (1935) research findings. He investigated the formation of group norms and conformity in an ambiguous situation (Sherif, 1935). This study relies on the autokinetic effect – an optical illusion that makes a stationary light appear to move when seen in complete darkness. Participants were led to believe that the experiment was investigating visual perception and told that the experimenter was going to move the light, something that was never done. The participants had to make 100 judgements as to how far the light, placed on the far wall of a darkened room, seemed to have moved.

To start with, participants made their judgements alone. Their estimates fluctuated for some time before converging towards a standard estimate, a personal norm. Such personal norms varied considerably between participants. In further sessions of 100 trials on subsequent days, the participants were joined by two other participants. They took turns in a random order to call out their estimates of the light’s movements. In this group condition, participants’ estimates soon reflected the influence of estimates from the others in the group. Eventually a common group norm emerged, a social norm, which was the average of the individual estimates. Different groups formed different group norms. Interestingly, the participants denied that their estimates were influenced by the other group members. During a third phase of the study, participants performed the task alone again; their estimates showed a continued adherence to the social norm established during the group session.

Here, because reality was ambiguous, participants used other people’s estimates as information to remove the ambiguity. Informational influence tends to produce genuine change in people’s beliefs thus leading to private conformity. Sherif’s work is important because it demonstrates how, at least in ambiguous settings, social norms can develop and become internalised (that is, function without the need of the actual presence of others). However, informational influence cannot be the only explanation for conformity, because conformity can be observed in situations where there is no ambiguity.

2. With reference to a study, explain conformity.

Conformity can be defined as adjusting one's behaviour or thinking to match those of other people or a group standard. There are lots of reasons why people conform, including the desire/need to fit in or be accepted by others and maintaining order in one’s life.

There are three major social influence processes which have been proposed to explain conformity, and these are informational influence, normative influence and referent informational influence. All of these explanations are, and some to a large extent, based on the influence of social norms. Social norms are group-held beliefs about how members should behave in a given context.

We are subjected to informational influence when we accept the views and attitudes of others as valid evidence about how things are in a particular situation. Having an accurate perception of reality is, of course, essential for our efficient functioning in our environment. Others are often viewed as valid sources of information, especially in situations where we cannot test the validity of our perceptions, beliefs and feelings.

Normative influence is another explanation of conformity. Normative influence underlies our conformity to the expectations of others. This type of influence is based on the need to be liked and accepted by others (the need to belong is one of the fundamental human motivations). In fear of social disapproval and rejection, we often behave in ways that conform to what others expect of us with little concern about the accuracy of beliefs we express or the soundness of our actions.

SIT theorists have developed the referent informational influence hypothesis, and this forms the basis of SIT explanations of conformity. From an SIT perspective, conformity is not simply a matter of adhering to just any social norms; it is more likely to do with adhering to a person’s ingroup norms. We conform out of a sense of belongingness and by doing so we form and maintain desired social identities. It follows from this that we are far more likely to conform to the norms of groups we believe we belong to and identify with.

Informational influence seems to be the most likely explanation for Sherif’s (1935) research findings. He investigated the formation of group norms and conformity in an ambiguous situation (Sherif, 1935). This study relies on the autokinetic effect – an optical illusion that makes a stationary light appear to move when seen in complete darkness. Participants were led to believe that the experiment was investigating visual perception and told that the experimenter was going to move the light, something that was never done. The participants had to make 100 judgements as to how far the light, placed on the far wall of a darkened room, seemed to have moved.

To start with, participants made their judgements alone. Their estimates fluctuated for some time before converging towards a standard estimate, a personal norm. Such personal norms varied considerably between participants. In further sessions of 100 trials on subsequent days, the participants were joined by two other participants. They took turns in a random order to call out their estimates of the light’s movements. In this group condition, participants’ estimates soon reflected the influence of estimates from the others in the group. Eventually a common group norm emerged, a social norm, which was the average of the individual estimates. Different groups formed different group norms. Interestingly, the participants denied that their estimates were influenced by the other group members. During a third phase of the study, participants performed the task alone again; their estimates showed a continued adherence to the social norm established during the group session.

3. Explain the strengths and limitations of one study on conformity

Informational influence seems to be the most likely explanation for Sherif’s (1935) research findings. He investigated the formation of group norms and conformity in an ambiguous situation (Sherif, 1935). This study relies on the autokinetic effect – an optical illusion that makes a stationary light appear to move when seen in complete darkness. Participants were led to believe that the experiment was investigating visual perception and told that the experimenter was going to move the light, something that was never done. The participants had to make 100 judgements as to how far the light, placed on the far wall of a darkened room, seemed to have moved.

To start with, participants made their judgements alone. Their estimates fluctuated for some time before converging towards a standard estimate, a personal norm. Such personal norms varied considerably between participants. In further sessions of 100 trials on subsequent days, the participants were joined by two other participants. They took turns in a random order to call out their estimates of the light’s movements. In this group condition, participants’ estimates soon reflected the influence of estimates from the others in the group. Eventually a common group norm emerged, a social norm, which was the average of the individual estimates. Different groups formed different group norms. Interestingly, the participants denied that their estimates were influenced by the other group members. During a third phase of the study, participants performed the task alone again; their estimates showed a continued adherence to the social norm established during the group session.

Here, because reality was ambiguous, participants used other people’s estimates as information to remove the ambiguity. Informational influence tends to produce genuine change in people’s beliefs thus leading to private conformity. Sherif’s work is important because it demonstrates how, at least in ambiguous settings, social norms can develop and become internalised (that is, function without the need of the actual presence of others). However, informational influence cannot be the only explanation for conformity, because conformity can be observed in situations where there is no ambiguity.

The strengths of Sherif’s study include the fact that it was pioneering and still remains one of the most influential experiments in social psychology today. It has generated a large amount of research, especially in the role of group norms on conformity behaviour. The study clearly demonstrates how a group norm can be established and then continues to influence a person’s judgement even when the social influence of the group is no longer present.

A minor limitation to this experiment surrounds the ethics of the deception involved. Participants were not informed about the purpose of the experiment (informed consent) but this was not the norm at the time of Sherif’s experiments, and the deception was arguably slight and necessary to avoid demand characteristics. Participants were debriefed at the end as to the true intents and purposes of the experiment. The major limitation is its lack of ecological validity. The task was artificial and ambiguous, and it is arguable that such ambiguous situations would never occur in real life situations. A possible counter argument to this criticism is that cognitive ‘anchoring’ can occur in our social groups. We have a tendency to use anchors or reference points to make decisions and evaluations, and sometimes these lead us astray. For example, if someone in my ingroup of girls informed me that 99% of teenage boys have body odour problems, then my perception of outgroup members on this domain will be influenced upwards towards this high initial anchor. Further, it turns out that we do not need the situation to be ambiguous for conformity to group norms to be observed.

We know you don't need reminding, but you should be well into your revision programme now. C'mon that IB Psychology 7!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed