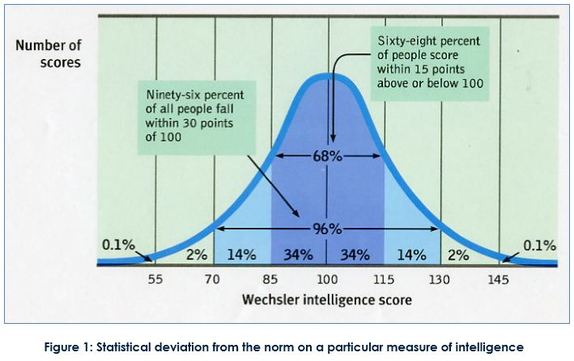

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent of mental disorders in the United States. Social Anxiety Disorder (social phobia) is a subset of anxiety disorders. A whopping 15 million individuals in the US, or 6.8 per cent of the total population suffer from social anxiety. It's equally prevalent between men and women, and individual onset is typically around 13 years of age. Lots of people live with it for a long time before seeking help. 36 per cent of those with social anxiety disorder live with the disorder for over 10 years before seeking help.

| The IB Psychology learning outcomes, which we all know by now are the examination questions, right? (see previous post), in the Abnormal option will ask students to learn and answer the following examination questions:

The majority of the content you will need to discuss and evaluate in the treatment of anxiety disorders will be psychotherapy and drugs. You will likely look at cognitive behavioural therapy. | Of course, you will need to be able to fully discuss and evaluate concepts, theories, models and studies relevant to anxiety treatments. But also, a great way to show the IB Psychology examiner that you are able to engage in and demonstrate your ability to think critically around this topic is to incorporate the study below into your answer. |

TRew and Alden (2015)Unsurprisingly, socially anxious people often avoid social interactions. They will go out of their way to limit their opportunities to engage in social interactions ("Sorry, I'm washing my hair that night, thanks.") and reduce the number of social interactions they engage in, such as the number of people they will interact with at a party they haven't been able to get out of. These two researchers found that people who were socially anxious were able to mingle more easily with other people in social situations if they busied themselves with acts of kindness. They split their participants into three groups. One group was asked to perform three acts of kindness for two days each week. THis could be mowing a neighbours lawns, giving to charity or cooking dinner for friends. Another was asked to engage in a social interaction three times for days each week. The final group was just asked to record what they had done each day. I know what you're thinking (and please make it clear to the IB Psychology examiner!), getting people to do acts of kindness forces those with social anxiety to go out there and interact with the people they're performing kind acts for. | TRew and Alden (2015) |

Traditional cognitive behavioural therapy works by the therapist asking her patient to imagine social situations while practicing mental relaxation techniques, to the point where they no longer feel intimidated by the thought of social interactions. This is then followed by a set of baby steps towards small scale social interaction (asking someone for the time, talking about the weather at the water cooler, etc.) while practicing the same relaxation techniques. Continuing on until the patient is comfortable in larger social situations like an office party or joining a club.

The acts of kindness study shows how cognitive behaviour therapy can be effectively and quickly modified. Social anxiety, by and large, is the result of individuals thinking about themselves too much. When they are in social situations they are monitoring their behaviour and constantly judging themselves as to how they might be being perceived by others they're interacting with. Stressful stuff. The Trew and Alden study shows that the best cognitive therapy is to get them doing nice things for others. This stops them thinking about themselves by forcing them to think of others instead. Once they're thinking about themselves less, they become naturally more relaxed in the presence of others. Boom! everyone's a winner ... the anxiety sufferers, the people receiving these acts of kindness, even you, as you receive full marks for critical thinking in your IB Psychology exam!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed