Craik and Lockhart's (1972) Level of Processing

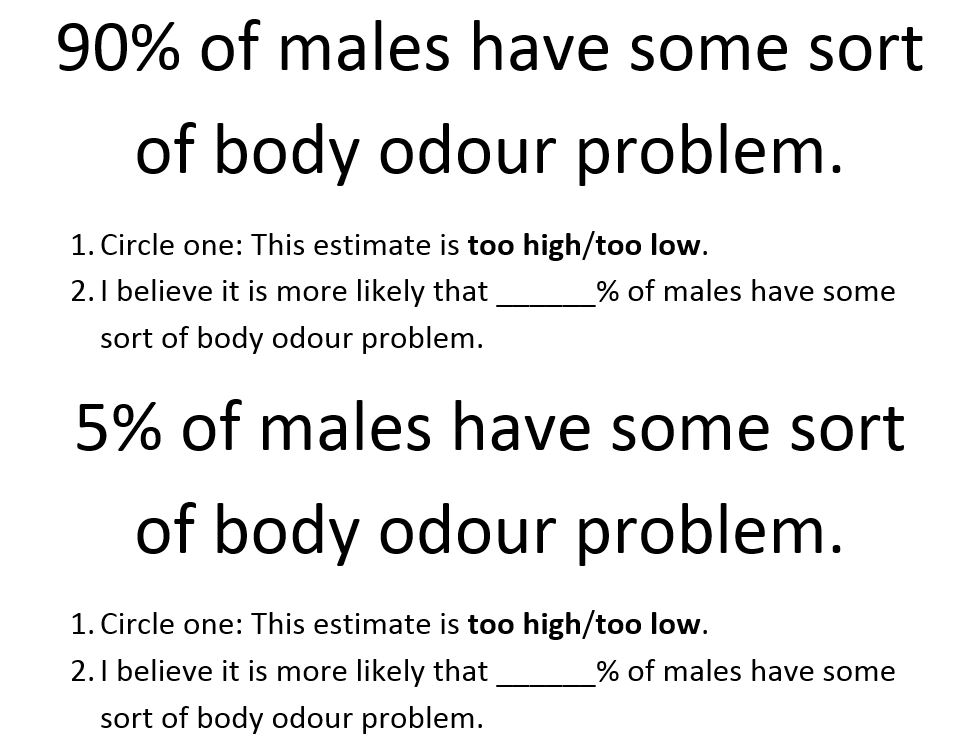

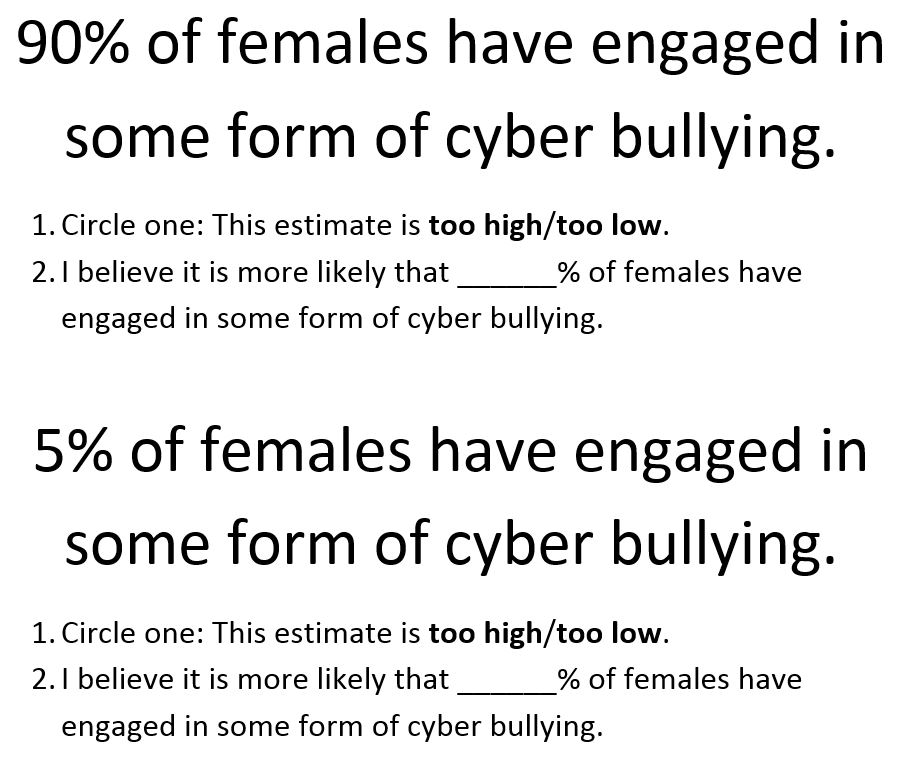

You read the script and have students record their answers. Next, you read the questions and have students answer on a separate piece of paper. Finally, you read the answers and have students mark their neighbour's responses. Record the results in a spreadsheet and use the data projector to display the results. Allow 30 minutes, including discussion time of the results.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed