| The best 5 tips from experienced IB Psychology teachers on how you can achieve that IB Psychology 7. | |

How to get a 7 in IB Psychology

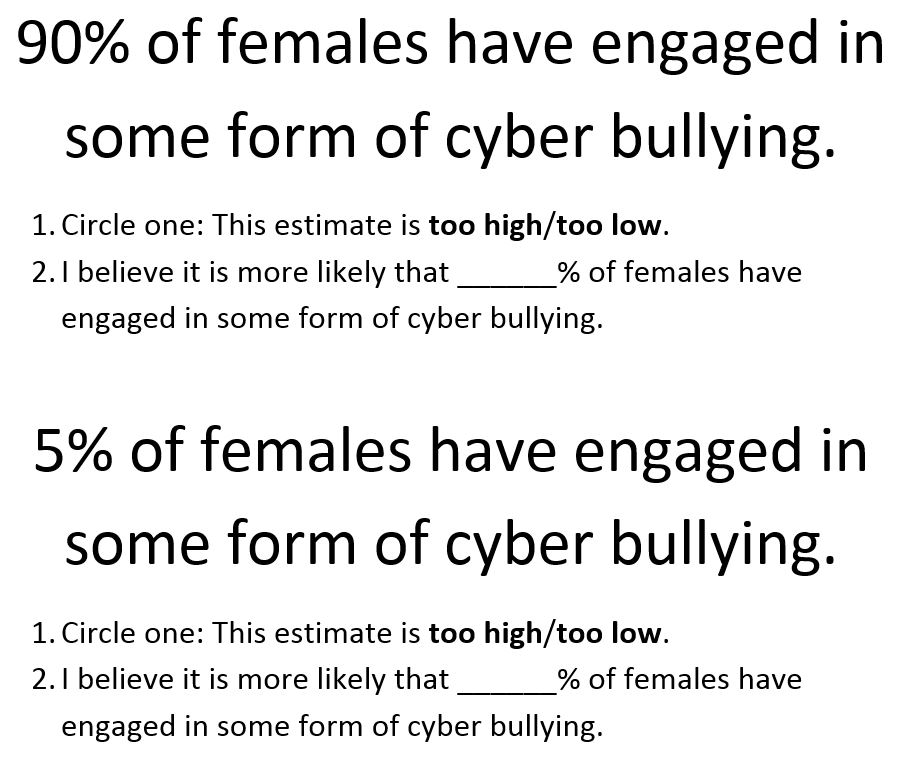

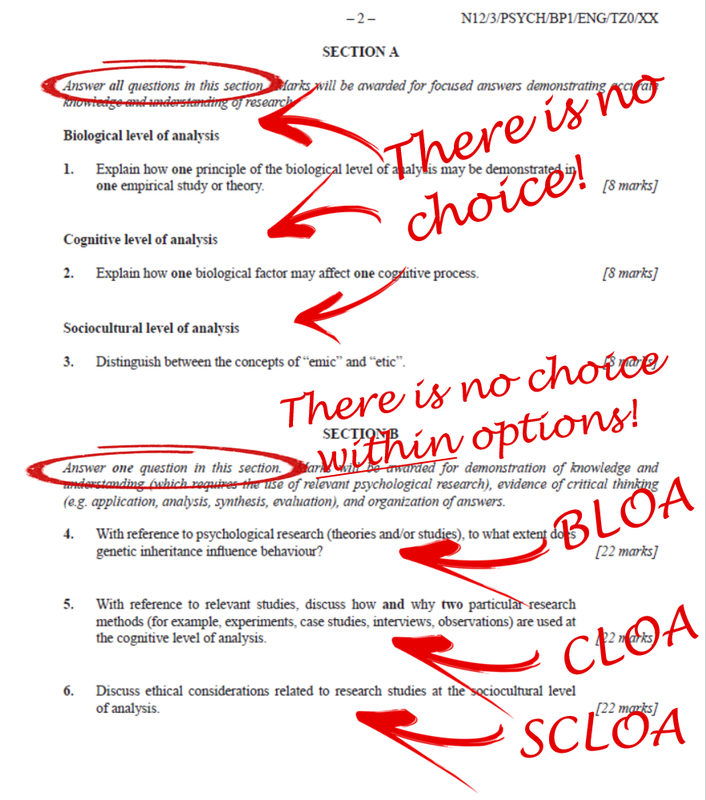

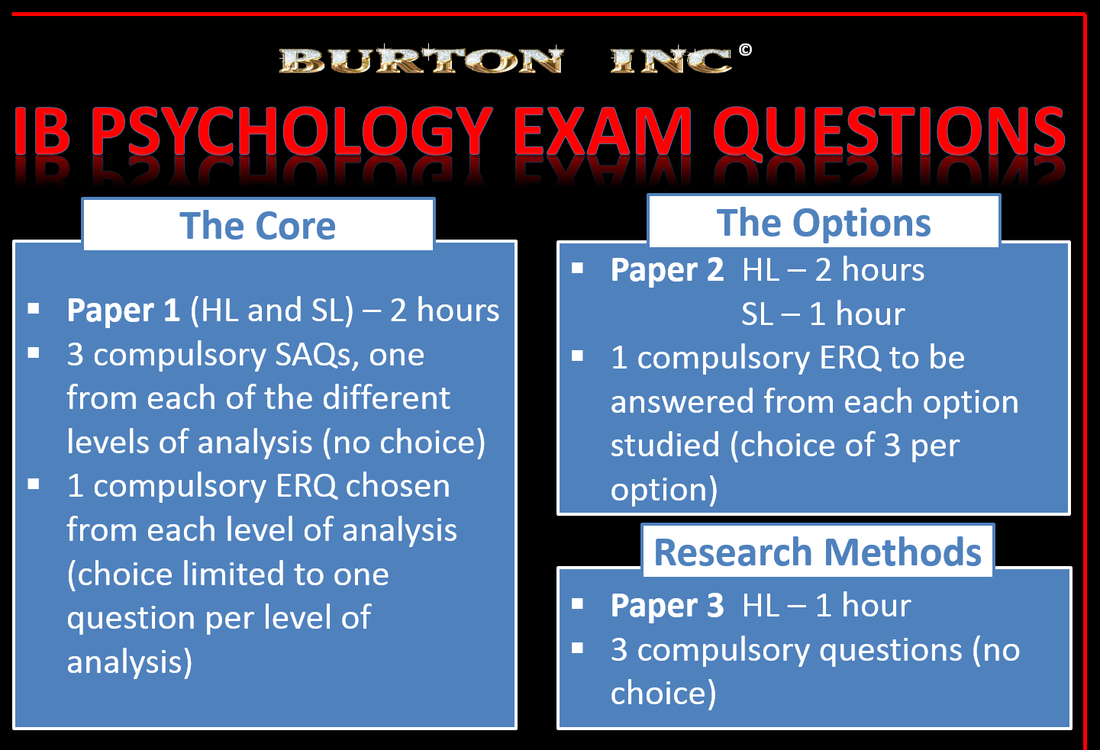

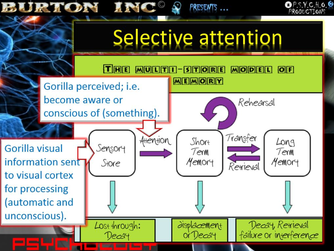

- You already know the questions that can be asked in all 3 of your IB Psychology examination papers! (Yes, really.)

- The IB Psychology Paper 1 examination has three sections - DO NOT study for two of these! (Yes, really.)

- Aim for maximum marks in your IB Psychology IA. (Almost goes without saying.)

- Prepare and memorise model answers to ALL of the extended response questions you are going to target in IB Psychology exams. (But be smart about it!)

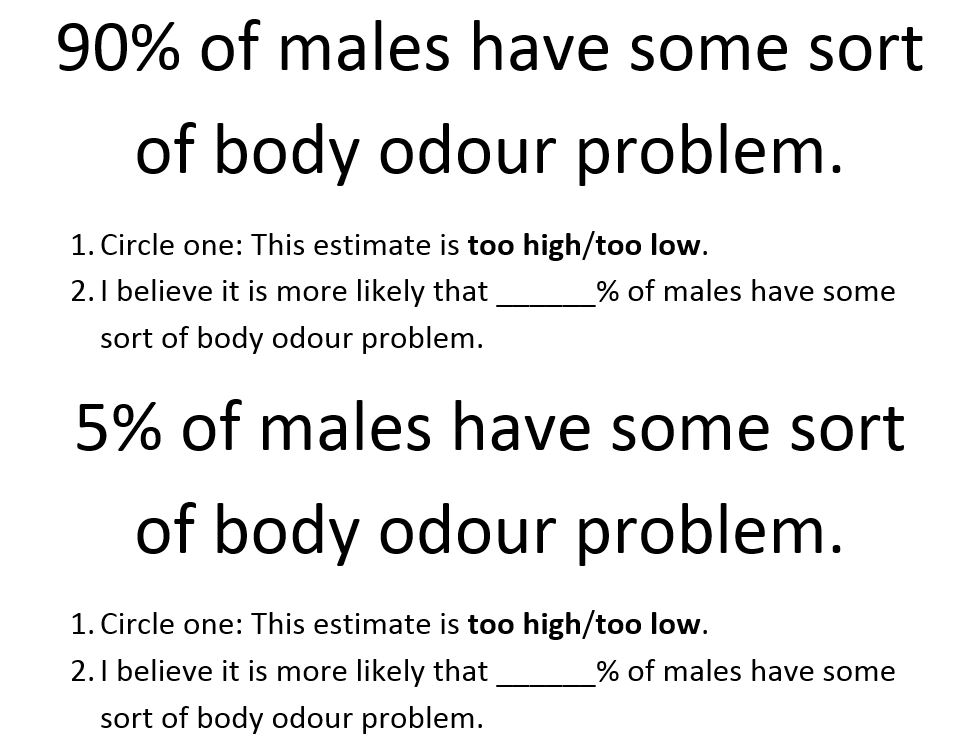

- Don’t ignore Qualitative Research Methods, because your IB Psychology teacher almost certainly will! (You need lots of practice with actual stimulus material - i.e., qualitative research)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed