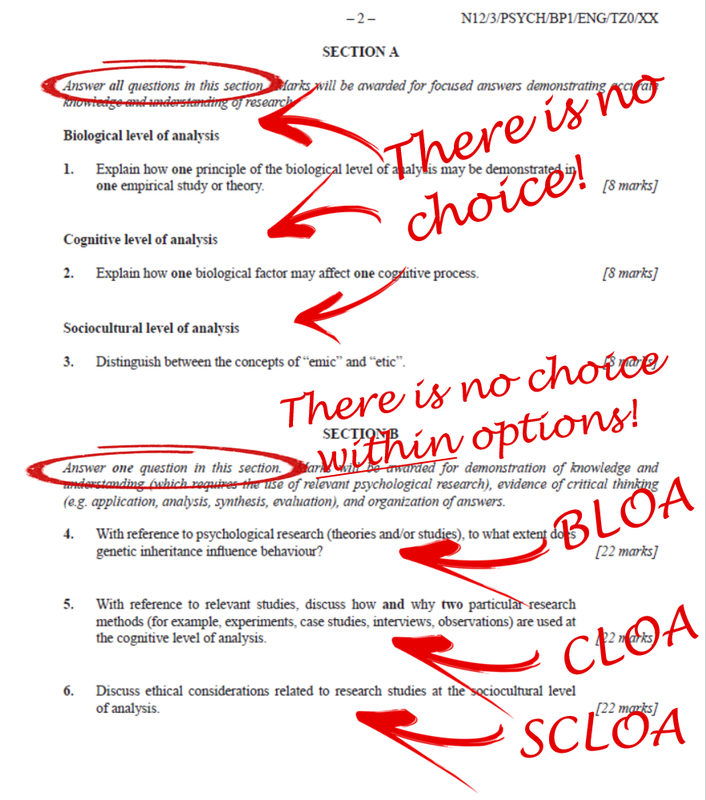

First you have to know, understand and have memorised the IB Psychology QRM content, next you have to practice applying that knowledge to the associated stimulus material.

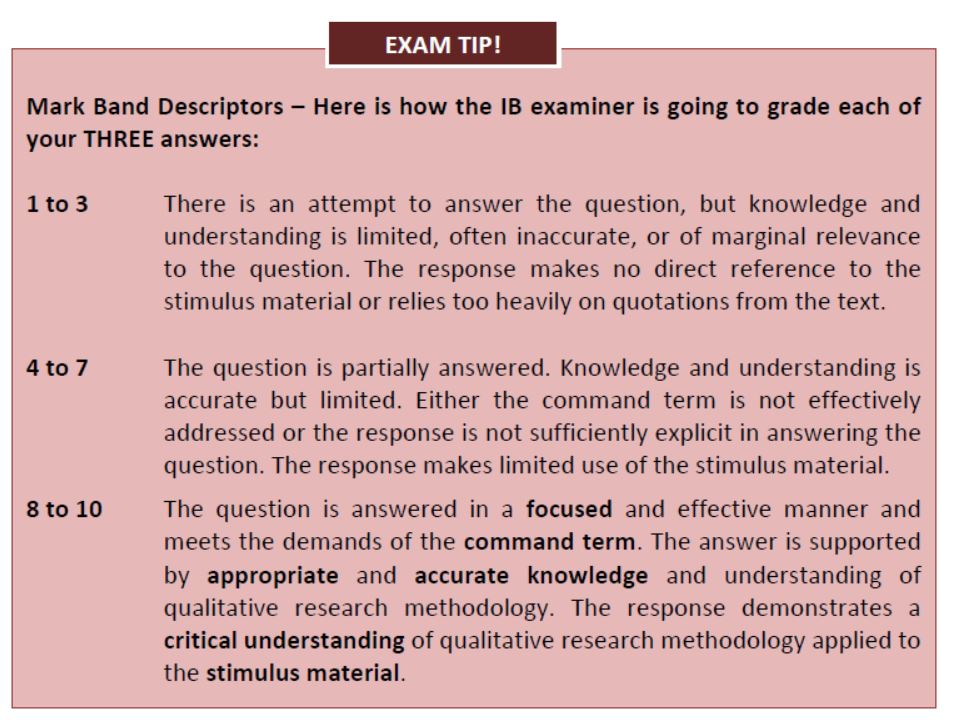

All IB Psychology Research Methods examinations follow the following structure. Approximately one page of stimulus material which outlines a piece of qualitative Psychological research (i.e., a study) followed by three 10 mark questions asking you to relate IB Psychology QRM learning outcomes to that piece of stimulus material.

IB Psychology has prepared an example Paper 3 examination question here for you to both familiarise yourself with and get in some valuable practice (IB Psychology exams are close now!).

IB PSychology Paper 3 exam stimulus material:

KIRA B. LEVY, KEVIN E. O'GRADY, ERIC D. WISH, and AMELIA M. ARRIA Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA.

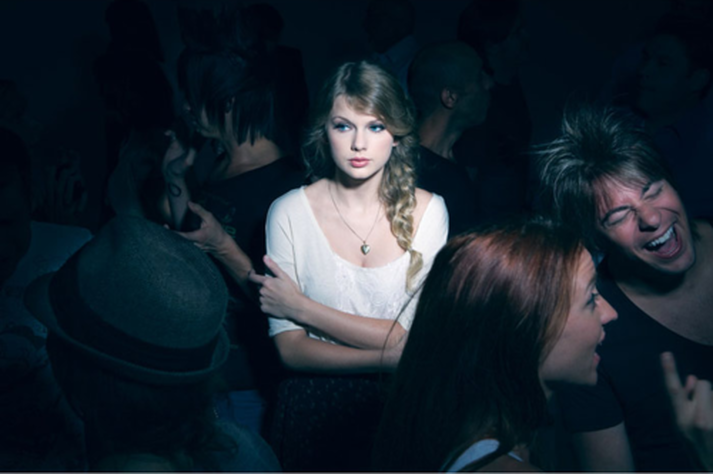

To obtain a sample, fliers were posted on a large 35,000-student campus, inviting individuals who had used ecstasy on at least one occasion to anonymously contact the researcher via telephone or e-mail using a fictitious first name if they were interested in participating in a focus group about ecstasy. Four focus groups of six to 10 individuals were held in a private room on campus (one male-only, one female-only, and two mixed-gender).

Upon entering the room for the focus group, each participant was instructed to write the fictitious first name they had used during the telephone screening on a name-tag. Participants were instructed to only use their fictitious first name during the session to protect their identity.

After completion of a brief survey, the guidelines for the hour-long group discussion were reviewed. Participants were told that they could speak about their personal experiences or what they knew about other substance users, without disclosing anyone's identity. Participants then engaged in a group discussion led by a facilitator. The facilitator moderated the discussion by asking specific questions and permitting group members to respond to the facilitator and to each other. The amount of time allotted to each topic varied based on group feedback and the judgment of the facilitator. The facilitator introduced each of six main topics, but discussion was not limited to these topics. Responses were written down by the facilitator and a trained research assistant.

Most participants had a basic understanding of the contents of ecstasy pills, and the effects that ecstasy has on the brain and bodily functions. Participants reported positive effects on mood, social pressure, curiosity, availability, boredom, desire for an altered state of mind, desire to escape, self-medication, desire to have fun, and the ease of use of ecstasy in comparison to other drugs as reasons for initiating ecstasy use. Participants described their experiences of both the positive and negative effects (physical and psychological) that they attributed to their use of ecstasy. The majority was unaware of specific types of problems ecstasy could potentially cause and discounted its potential harm.

At the conclusion of the group discussion, the moderator provided participants with a list of mental health resources and an informational hand-out about ecstasy containing a list of websites pertaining to substance use.

1. Evaluate the use of a focus group for this study. [10 marks]

2. Discuss the sampling technique used for this study. [10 marks]

3. To what extent could findings from this study be generalised? [10 marks]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed