| A model ERQ answer on bystanderism A model answer to an IB Psychology Human Relationships extended response question. For sure, the perfect answer to an IB Psychology extended response question is very difficult to write. Luckily for you, we here at IB Psychology specialise in helping teachers teach and students learn how to write these perfect answers. To this end, we like to provide students and teachers of the course with plenty of exemplars they can be using in the Psychology classroom to demonstrate all of the requirements that a perfect answer needs to fulfill. We know it's not easy, but on the up side, for each perfect answer you manage to produce, there is every chance that the IB Psychology exam will ask you the exact same question. So, if you produce enough model ERQ answers, practice and memorise them, you will astonish your IB examiners. This is how you get the IB Psychology 7. | Having a set of IB Psychology model answers will be worth all of the hard work that goes into preparing them. In this blog post we bring you the model ERQ answer to the IB Psychology learning outcome: Examine factors influencing bystanderism - in the Human Relationships option. |

Examine factors influencing bystanderism

The back ground for research on bystanderism was the Kitty Genovese murder in New York City in 1964. She was attacked, raped and stabbed several times over a period of 30 minutes by a psychopath. Later a large number of witnesses that they had heard screaming or seen a man attacking the woman (38 later testified as having heard her screams), yet none of them had intervened or called the police until it was too late. Afterwards they said that they did not want to become involved or thought that someone else would intervene. Researchers here established a cognitive model to explain the decision an individual makes to act or not. One of the key conclusions they drew was that the number of bystanders present has an enormous influence on the likelihood that one of them will help.

This essay will address two theories regarding factors that influence bystanderism: the theory of the unresponsive bystander and the cost-reward model of helping, before examining the role of individual personality characteristics.

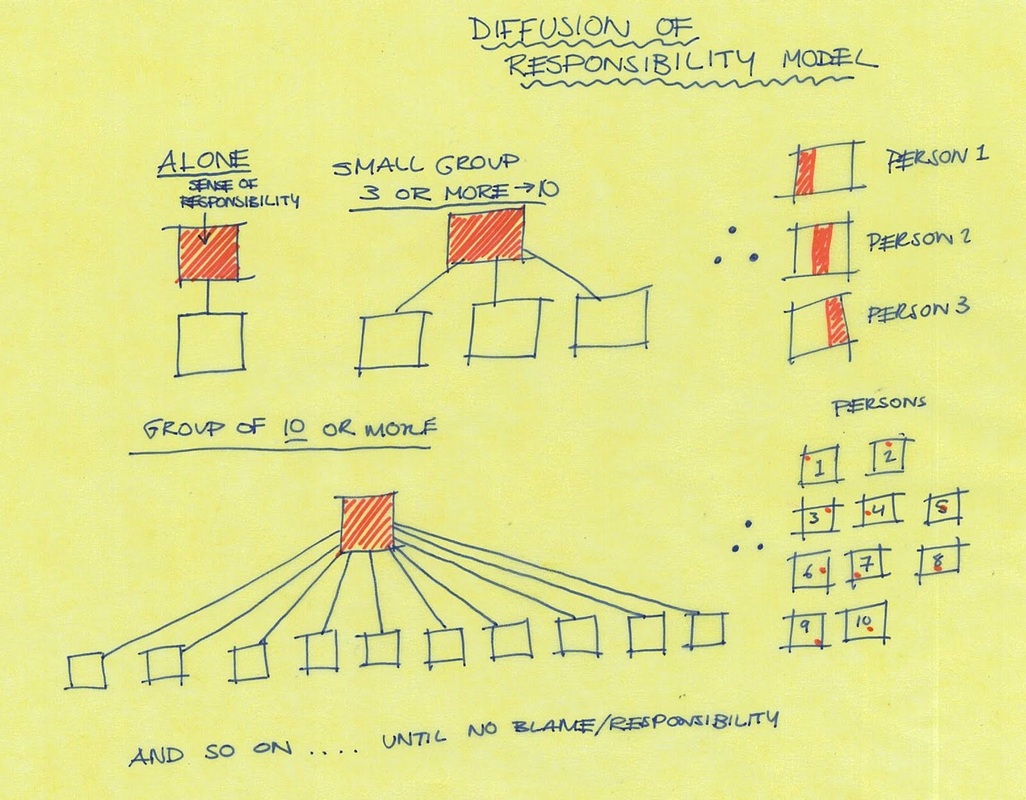

- Diffusion of responsibility: When you are the only person who can deal with an emergency situation, you have 100 per cent of the responsibility to do so (whether you actually choose to intervene or not). However, with more witnesses, each individual’s share of the responsibility drops (see figure 1) and this reduces the psychological costs of not intervening.

- Social influence: It may be that in an ambiguous social situation, we look to the actions of others for guidance (social influence). This inaction breeds more inaction, in that if we see others not doing anything, we may feel that it is not necessary to do something. If we observe five people walking in front of us pass by a man slumped over on the pavement, then that may go some way to resolving in our own minds as to whether or not he really needs help.

- Audience inhibition: On the other hand, we may be afraid of appearing to overreact or of making some kind of social blunder (thus, audience inhibition). So, if individual bystanders are aware that other people are present they may be afraid that any action they take may be evaluated negatively. In terms of Latane & Darley’s model, this forms part of a person’s judgement about whether intervention is necessary or appropriate. Imagine the embarrassment of offering to help someone who does not need help.

Latane & Darley (1968) suggested a cognitive decision model. They argue that helping requires the bystander to:

- Notice the situation – if you are in a hurry to get somewhere you may not even be aware of what is going on).

- Interpret the situation as an emergency – for example, people screaming or asking for help which could also be interpreted as a family quarrel which is none of your business.

- Accept some personal responsibility for helping even though others are present.

- Consider how to help – although you may be unsure of what to do or doubt your skills.

- Decide how to help – you may observe how other people react and decide not to intervene.

At each of these stages, the bystander can make a decision to help or not.

Latane & Darley (1968) conducted an experiment to investigate bystander intervention and diffusion of responsibility.

Aim: To investigate if the number of witnesses of an emergency influences people’s helping in an emergency situation.

Procedure: As part of course credit, 72 students (59 female and 13 male) participated in the experiment. They were asked to discuss what kind of personal problems new college students could have in an urban area. Each participant sat alone in a booth with a pair of headphones and a microphone. They were told that the discussion took place via an intercom to protect the anonymity of participants. At one point in the experiment a participant (confederate) staged a seizure. The independent variable (IV) of the study was the number of persons (bystanders) that the participant thought listened to the same discussion. The dependent variable (DV) was the time it took for the participant to react from the start of the victim’s fit until the participant contacted the experimenter.

Results and conclusion: The number of bystanders had a major effect on the participant’s reaction. Of the participants in the alone condition, 85% went out and reported the seizure. Only 31% reported the seizure when they believed there were four bystanders. The gender of the bystander did not make a difference.

Ambiguity about a situation and thinking that other people might intervene (i.e., diffusion of responsibility) were factors that influenced bystanderism in this experiment.

During debriefing students answered a questionnaire with various items to describe their reactions to the experiment, for example “I did not know what to do” (18 out of 65 students selected this) or “I did not know exactly what was happening” (26 out of 65) or “I thought it must be some kind of fake” (20 out of 65).

Evaluation: There was participant bias (psychology students participating for course credits). Ecological validity is a concern due to the artificiality of the experimental situation (e.g., the laboratory situation and the fact that bystanders could only hear the victim and the other bystanders could add to the artificiality. Finally, there are ethical considerations in that participants were deceived and exposed to an anxiety-provoking situation.

Another theory about factors affecting bystanderism was developed by Pilliavin et al. (1969). This is the cost reward model of helping, and the theory stipulates that both cognitive (cost-benefit analysis) and emotional factors (unpleasant emotional arousal) determine whether bystanders to an emergency will intervene. The model focuses on egoistic motivation to escape an unpleasant emotional state (opposite of altruistic motivation). Empathy evokes altruistic motivation to reduce another person’s distress whereas personal distress evokes an egoistic motivation to reduce one’s own distress, or recognition that helping will produce a reward (e.g., strong feeling of virtuousness or social approval). The theory was suggested based on a field experiment in New York’s subway.

The subway Samaritan (Pilliavin, 1969)

Aim: The aim of this field experiment was to investigate the effect of various variables on helping behaviour.

Procedure:

- Teams of students worked together with a victim, a model helper, and observers. The IV has whether the victim was drunk or ill (carrying a cane), and black or white.

- The group performed a scenario where the victim appeared drunk or a scenario where the victim appeared ill.

- Participants were subway travellers who were observed when the ‘victim’ staged a collapse on the floor a short time after the train had left the station. The model helper was instructed to intervene after 70 seconds if no one else did.

Results and conclusion: The results showed that a person who appeared ill was more likely to receive help than one who appeared drunk. In 60% of the trials where the victim received help more than one person offered assistance. The researcher did not find support for diffusion of responsibility. They argue that this could be because the observers could clearly see the victim and decide whether or not there was an emergency situation. Pilliavin et al. found no strong relationship between the number of bystanders and the speed of helping, which is contrary to the theory of the unresponsive bystander.

Evaluation: This study has higher ecological validity than laboratory experiments and it resulted in a theoretical explanation of factors influencing bystanderism. Based on this study the researchers suggested that the cost-reward model of helping involves observation of an emergency situation that leads to an emotional arousal and an interpretation of that arousal (e.g., empathy, disgust, fear) this serves as a motivation to either help of not, based on an evaluation of costs and rewards of helping:

- Costs of helping (e.g., effort, embarrassment, physical harm)

- Costs of not helping (e.g., self-blame and blame from others)

- Rewards of helping (e.g., praise from the victim and self)

- Rewards of not helping (e.g., being able to continue doing whatever one was doing.

Evaluation of the model: The model assumes that bystanders make a rational cost-benefit analysis rather than acting intuitively and on impulse. It also assumes that people only help for egoistic reasons, which is probably not true. Most of the research on bystanderism is conducted as laboratory or field experiments but findings have been applied to explain real-life situations.

Another key point to consider when examining factors that influence bystanderism that neither the theory of the unresponsive bystander or the cost reward model of helping takes into consideration, is that there is significant individual variance that cannot be wholly attributable to the situation. Dispositional or personality characteristics are important in determining whether someone will help or not in an emergency situation.

There is evidence that dispositional factors and personal norms are influential in determining the likelihood of bystanderism in an individual. Oliner & Oliner (1988) examined dispositional factors and personal norms in helping in an emergency situation, in this case, the Holocaust. The Holocaust was an exceptional life threatening emergency situation for the European Jews. Witnesses to the deportation of Jews all over Europe reacted in different ways. Some approved of the anti-Semitic policies, many were bystanders and a few risked their own life to save Jews. Within the context of the Second World War, saving Jews was a risky behaviour because it was illegal in many countries and the Jews were socially marginalised (pariahs). Despite this, some people decided to help (act altruistically). Heroic helpers such as those who saved Jews under the Holocaust (e.g., Oscar Schindler of ‘Schindler’s List fame) may have strong personal norms. Those that risk their lives to help others in situations like the Holocaust often deviate radically from the norms of their society.

Oliner & Oliner (1988) examined the role of dispositional factors and personal norms in helping. These researchers interviewed 231 Europeans who had participated in saving Jews in Nazi Europe and 126 other similar people who did not rescue Jews. Of the rescuers, 67% had been asked to help, either by a victim or by someone else. One they had agreed to help they responded positively to subsequent requests.

Results showed that rescuers shared personality characteristics and expressed greater pity or empathy compared to non-rescuers. Rescuers were more likely to be guided by personal norms (high ethical values, belief in equity, and perception of people as equal). Rescuers often said that parental behaviour had made an important contribution to the rescuer’s personal norms. For example, the parents of rescuers had few negative stereotypes of Jews compared to non-rescuers. The family of rescuers also tended to believe in the universal similarity of all people.

Other factors such as similarity, victim attributes, responsibility, mood, competence and experience can also influence the degree of bystandersim in any person or emergency situation. These factors are not considered in the two models examined here, but have been shown to of some importance.

General conclusion

Both the theory of the unresponsive bystander and the cost-reward model of helping are cognitive models of decision making where individuals weigh up several factors regarding the emergency situation, consciously or unconsciously, before making their decision to help or not. Both of these models have good predictive power as to how people will behave in real life emergency situations; however each does have its own limitations. Neither of these models takes into account the influence of personality factors, which may be of considerable influence in bystanderism.

Word count: 2 000

RSS Feed

RSS Feed