Find below my personal list of handy hints that I share with my IB Psychology students:

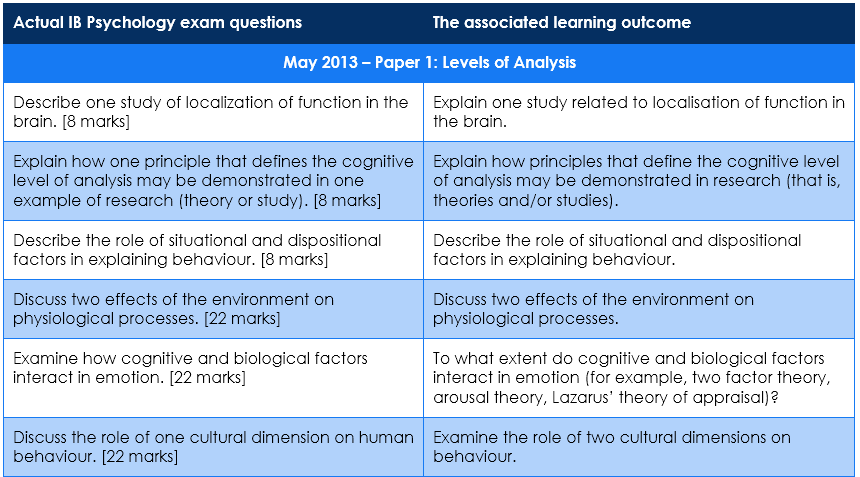

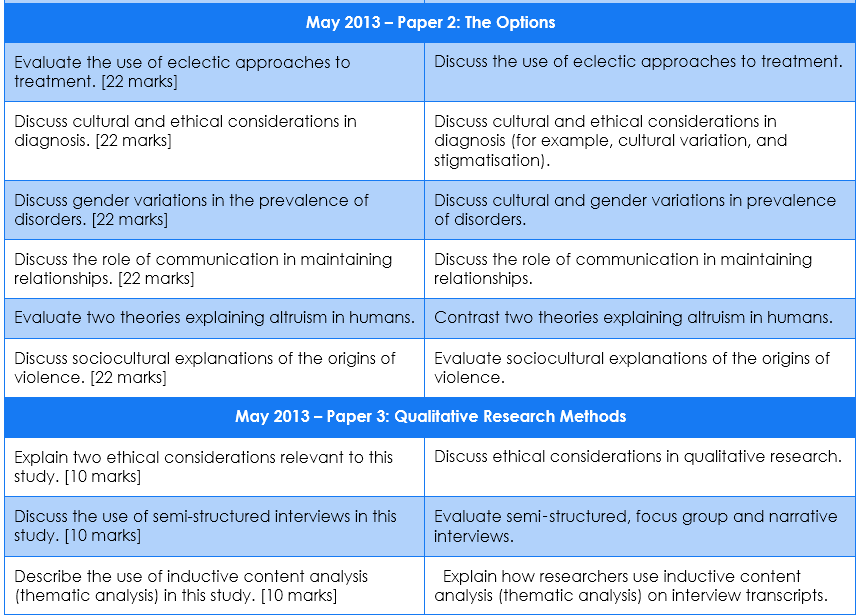

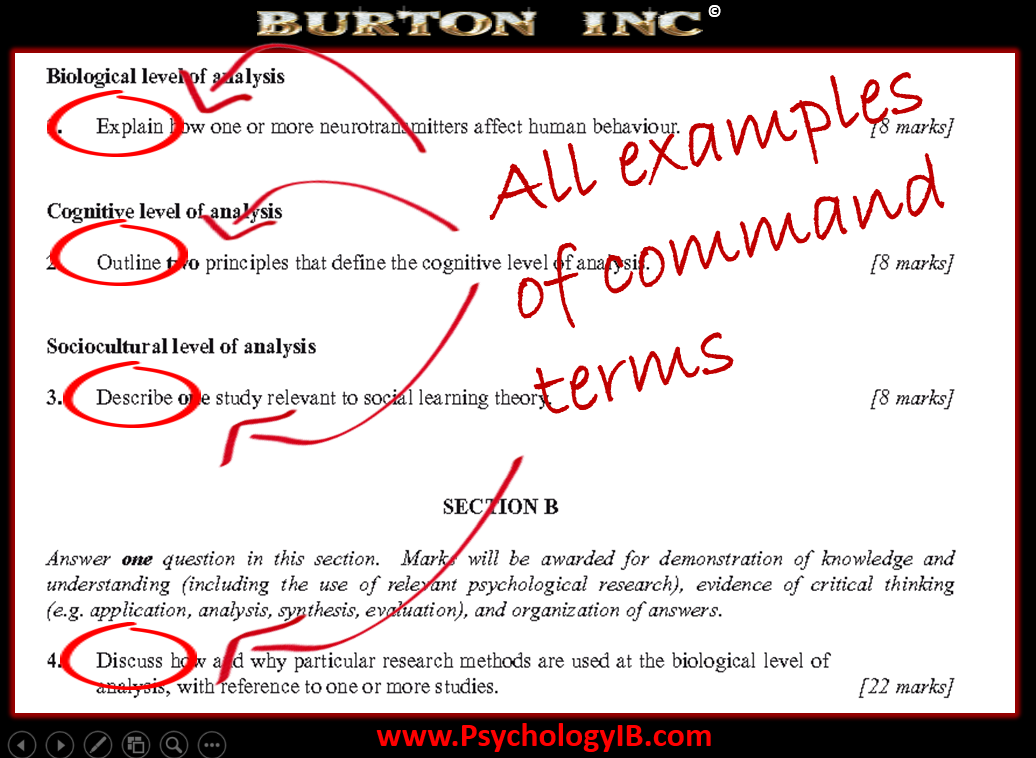

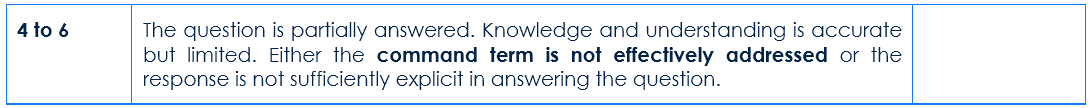

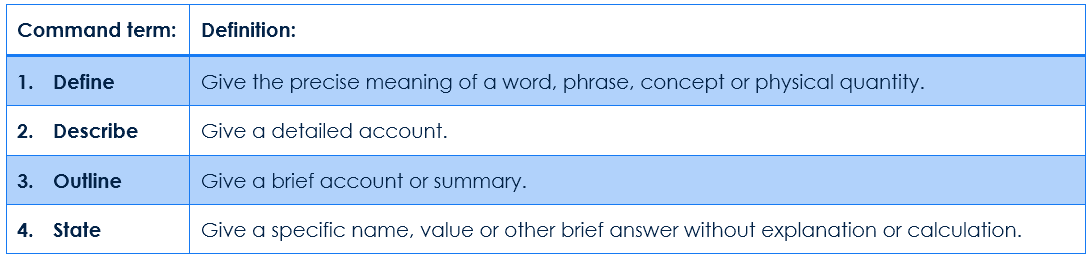

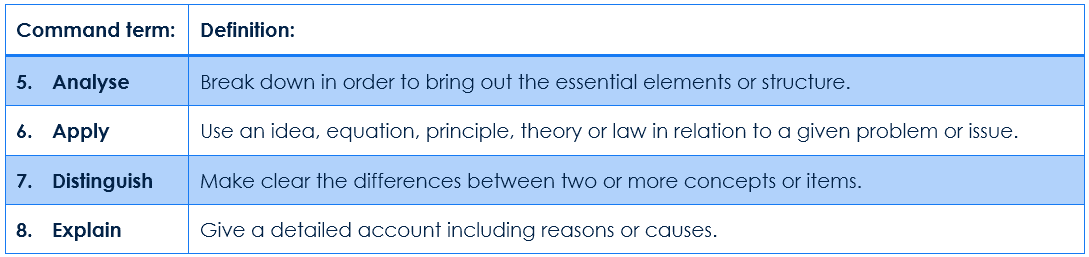

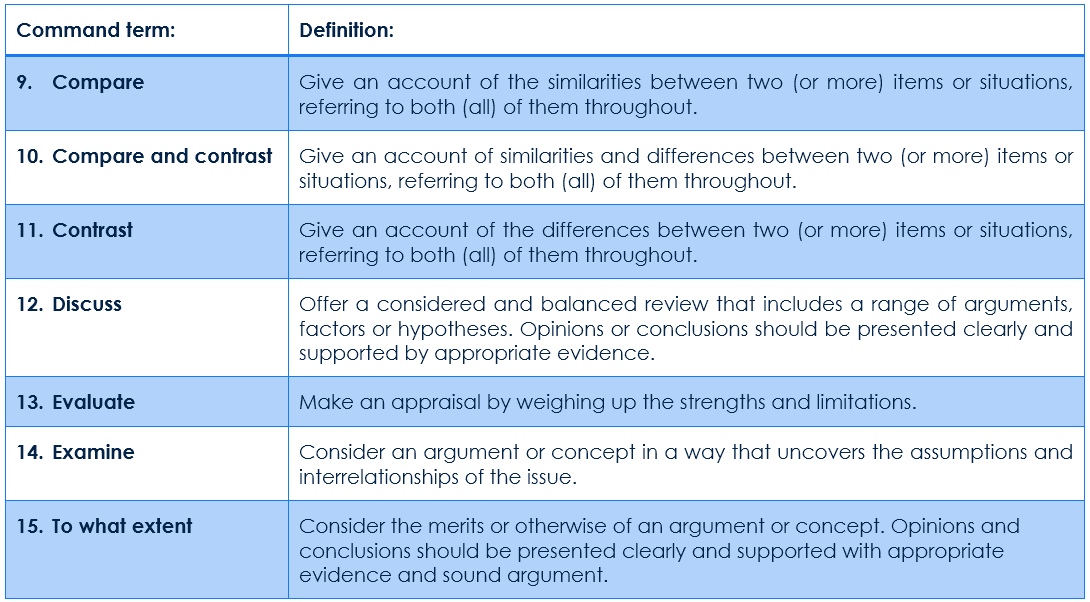

- Make sure you understand the command term and know the difference between explain or discuss or whatever you might be asked to demonstrate your understanding of the IB Psychology learning outcome

- Define the keywords in the IB Psychology SAQ and integrate the definitions into a “In other words…” sentence.

- Make sure you use the words from the question in your answer at least two or three times. If the IB Psychology SAQ is about physiology use this word rather than brain or body.

- Use studies to support your explanations. Give a brief summary of the study and then explain why this is relevant.

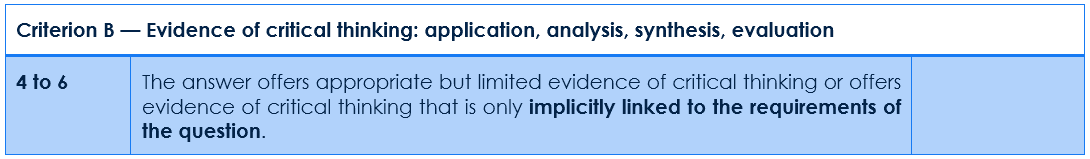

- Take every opportunity to evaluate the study but do not just outline every strength and limitation, only the relevant ones. For example there is no need to discuss ethical considerations with the Davidson meditation study from the BLOA but the small sample size is relevant as it makes generalising his finding that cognition can change brain physiology more limited.

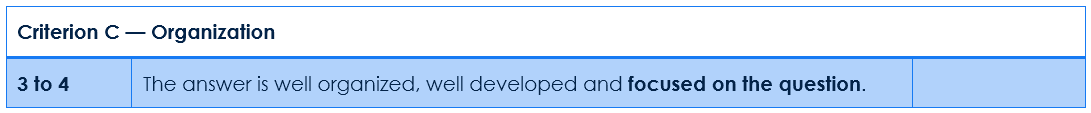

- Aim for a short introduction and conclusion. These can be just one sentence in length. If you are asked about two hormones or two studies or two neurotransmitters make sure you have two body paragraphs.

A perfect IB Psychology SAQ exam anser

It is assumed that they are highly resistant to forgetting; i.e., the details of the memory will remain intact and accurate because of the emotional arousal at the moment of coding. For example, some individuals can report in exceptional exactly when and how they heard the news of the September 11 terrorist attacks on the USA in 2001, as well as exactly what they were doing at the time and their exact feeling and reactions in response to the news – i.e., an exceptionally detailed and vivid memory almost twenty years after the fact. There is a posited relationship between strong emotion at the time of encoding and the exceptional details of these memories.

Brown and Kulik (1977) – research on FBM

Aim: To investigate whether shocking events are recalled more vividly and accurately than other events.

Procedure: 80 US participants were asked questions about 10 events. Nine of the events were mostly assassinations or attempted assassinations of well-known American personalities (e.g., JF Kennedy, Martin Luther King). The tenth was a self-selected event of personal relevance and involving unexpected shock. Examples included the death of a friend or relative or a serious accident.

Participants were asked to recall the circumstances they found themselves in when they first heard the news about the 10 events. They were also asked to indicate how often they had rehearsed (overtly or covertly) information about each event.

Results and conclusion:

- Participants had vivid memories of where they were, what they did, and what they felt when they first heard about a shocking public event

- The participants also said they had FBMs of shocking personal events

- The results indicated that FBM is more likely for unexpected and personally relevant events. This lead the researchers to suggest ‘the photographic nature of FBM’

- Brown & Kulik suggest that FBM is caused by the physiological emotional arousal (e.g., activity in the amygdala).

However, findings from this study are clearly consistent with Brown & Kulik’s theory. Additional support comes from a study by Conway et al. (1994) who studied FBMs of both UK and non-UK citizens of the unexpected resignation of a famous (or infamous) British Prime Minister – Margaret Thatcher. Data was collected at several points including a few days after the resignation and after 11 months. They found that 85% of UK citizens and considerably fewer non-UK citizens had an FBM at 11 months.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed