|

We show you exactly what you can get away with when revising for your IB Psychology Paper 2 exams – the Options.

|

|

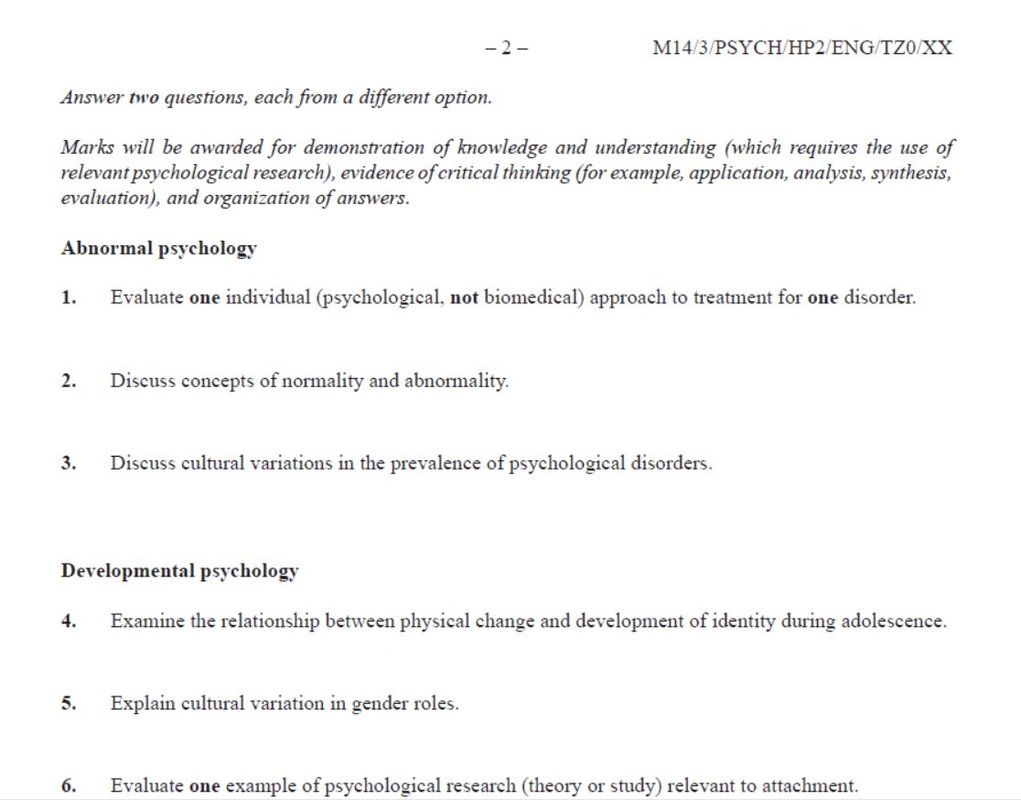

Take a look at picture below left (click to enlarge). You will see that there are three questions associated with each option, of which you only need to answer one. You will know by now that each question asked in the IB Psychology examinations is straight out of the learning outcomes listed in the IB Psychology Guide (if not, please see one of most popular blog posts here).

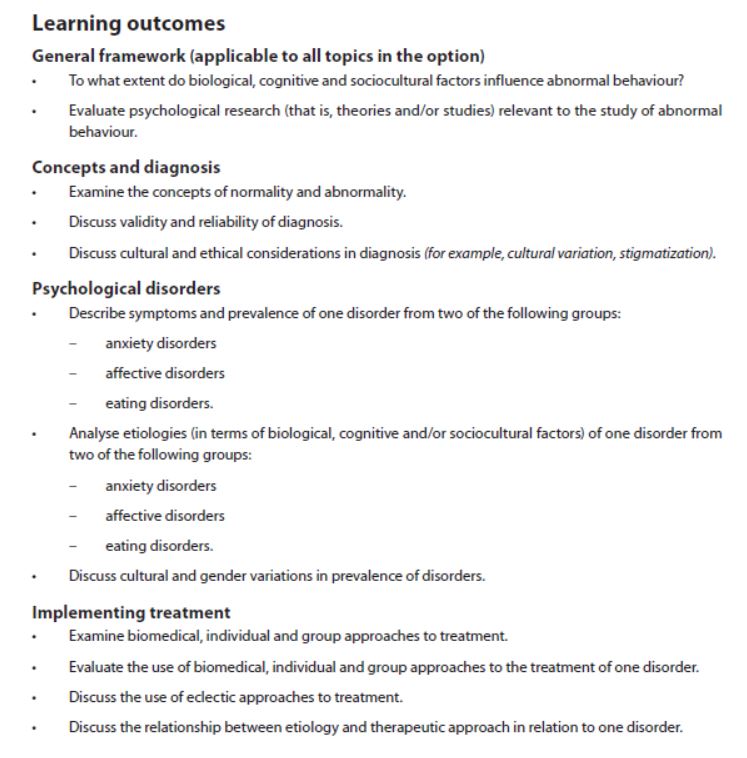

Firstly, within each option you have three essay question (ERQ) choices. Secondly, there has never been, nor is there likely to ever be, an IB Psychology exam where all three questions come from within a single subsection such as “Concepts and Diagnosis” or “Psychological Disorders” in the Abnormal option. This means that you can eliminate one ERQ from each of these sections. Thirdly, IB Psychology examiners can’t set an ERQ exam question based on a lower level command terms such as “explain”, “analyse” or “describe”. Very occasionally you will see exam question twisted and contorted to mix a lower level question term and a higher level command term. It hardly ever happens, you have other questions to choose from, so go ahead, cross these LOs off your list too.

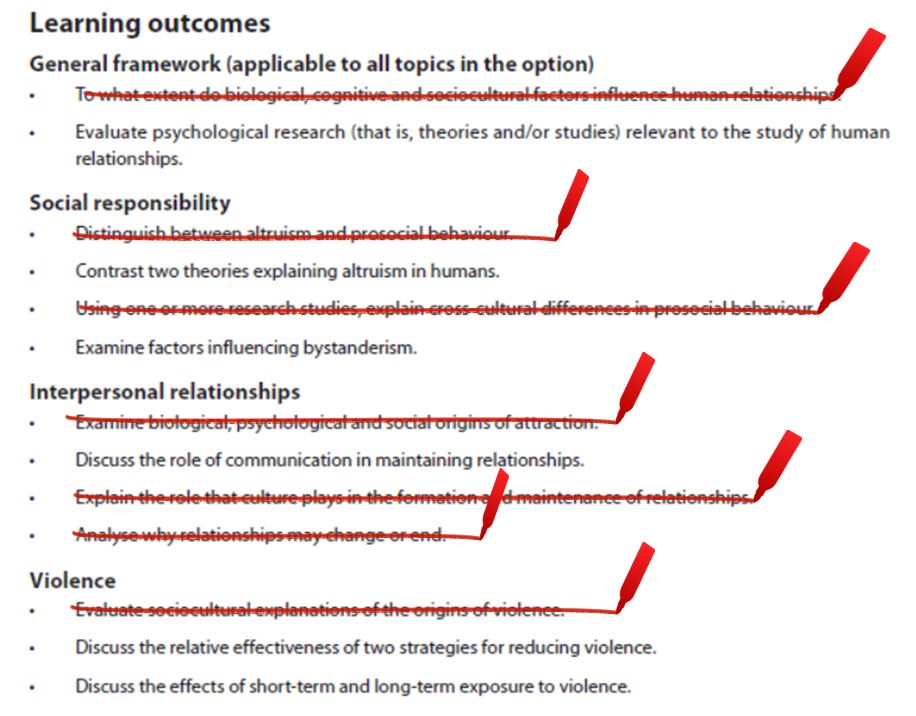

Take a look below (again, click to enlarge) at how many Human Relationship LOs you will need to prepare model answers and revise for if you follow this advice. Instead of revising for 13 LOs, you now only need prepare and revise for six! And because you are now only focussing on six ERQ questions, you can prepare perfect 22/22 answers, commit them to memory and regurgitate them as soon as the IB Psychology Paper 2 exam begins. Genius! (At least your IB Psychology examiner will think you are!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed