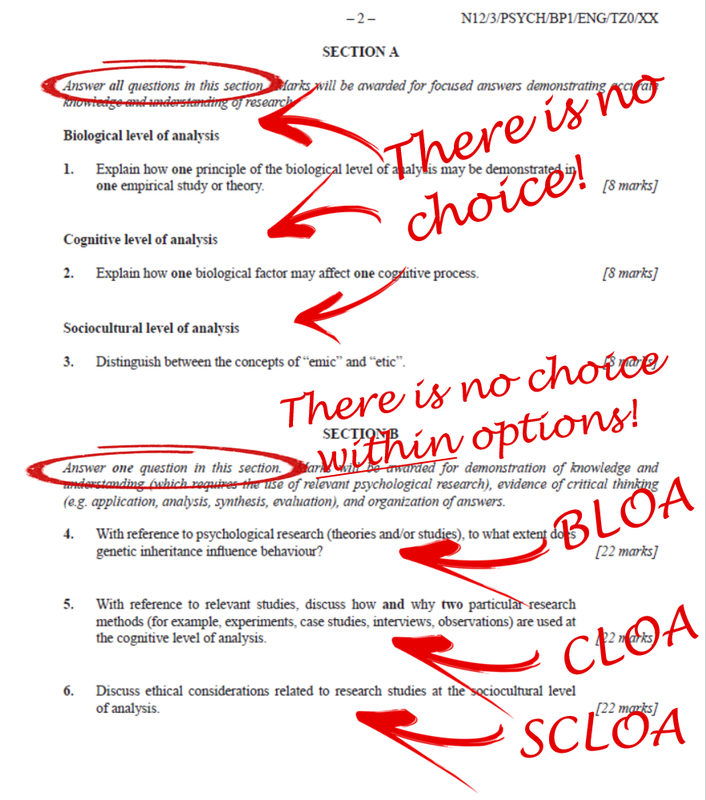

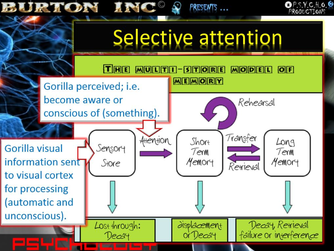

Just beware, diagrams and illustrations that you use in your IB Psychology answers need to be referred to in the text you write (i.e., "... as can be seen in figure 1., the ..."). Those marking the IB Psychology exams are not required to search backwards and forwards through your written response and guess when, where and how the perfectly good flowchart they see before them, ties in with the answer you have provided. So, signpost it.

A model short answer response to the IB Psychology Socio-cultural Level of Analysis learning outcome: Explain Social Learning Theory, is provided below. This model IB Psychology examination answer incorporates the correct use of a flowchart.

We learn consequences of behaviour from watching what happens to other humans (vicarious reinforcement). Once such information is stored in memory it serves to guide further actions. People are more likely to imitate behaviour that has positive consequences. Social learning can be direct via instructions (e.g., role models and no direct instructions).

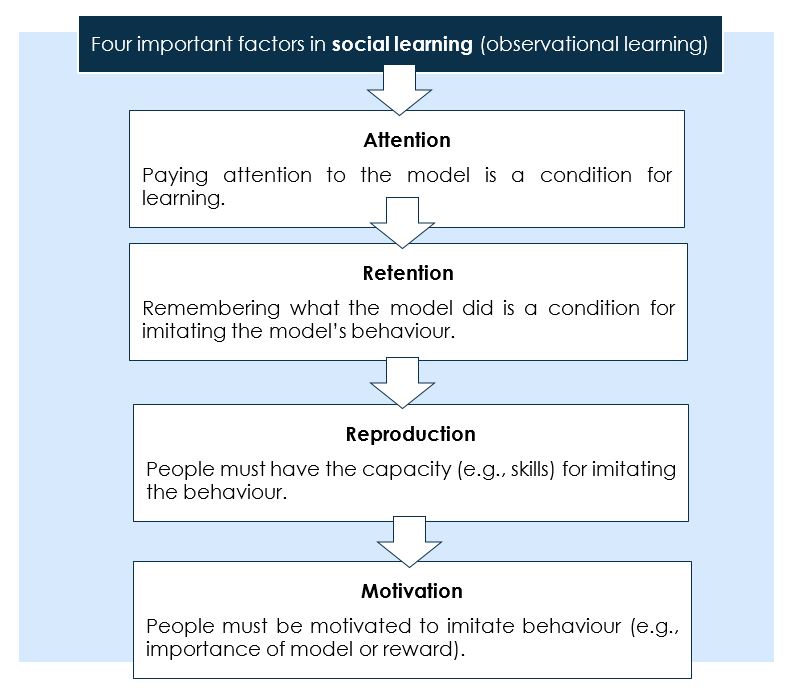

Figure 1 below, outlines the important factors that facilitate social learning.

Aim: To see if children would imitate the aggression of an adult model and whether they would imitate same-sex models more than opposite-sex models.

Procedure:

- Participants were 36 boys and 36 girls from the Stanford University nursery school (mean age 4.4) who were divided into three groups matched on levels of aggressiveness before the experiment.

- One group saw the adult model behave aggressively towards bobo doll, one group saw the model assemble toys, and the last group served as the control.

- The children were further divided onto groups so that some saw same sex models and some saw opposite sex models.

- The laboratory was set up as a play room with toys and a bobo doll. The model either played with the toys or behaved aggressively towards the bobo doll. After seeing this, the children were brought into a room with toys and told not to play with them in order to frustrate them. They were the taken into a room with toys and a bobo doll where they were observed for 20 minutes through a one-way mirror.

Results:

- Children who had seen an aggressive model were significantly more aggressive (physically and verbally) towards the bobo doll. They imitated the aggressive behaviour of the model but also showed other forms of aggression.

- Children were also more likely to imitate same-sex models. Boys were more aggressive overall than girls.

- Conclusions:

- This key study supports social learning theory. Aggressive behaviour can be learned through observational learning.

- It is not possible to conclude that children always become aggressive when they watch violent models (e.g., on television or at home). Generally, research supports that children tend to imitate same-sex models more and this is also the case for adults.

- The laboratory experiment is low on ecological validity. The aggression here is artificial and there may be demand characteristics. The children were very young and it has been criticised for ethical reasons.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed