Here, I am sharing with you the best five strategies I have for achieving that very, very elusive IB Psychology 7. Remember, just three per cent of all Higher Level IB Psychology students achieve the maximum mark of 7.

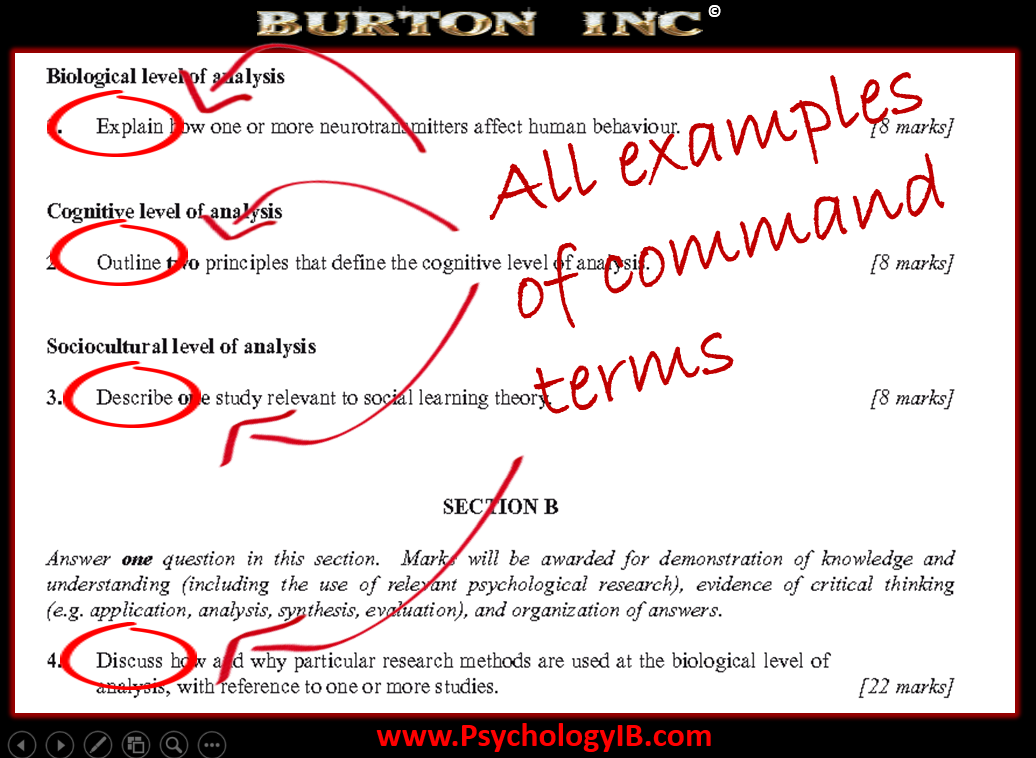

The IB Psychology Paper 1 examination has three sections - DO NO study for two of these!

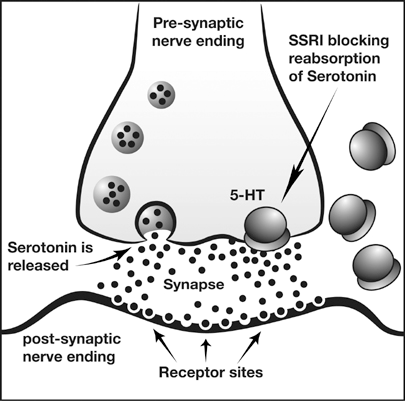

Choose one of either the IB Psychology Biological Level of Analysis, The Cognitive Level of Analysis or the Socio-Cultural Level of Analysis. Focus your study and preparation here and get really good at this one section. This section will bring you 30 marks out of a total 46.

Our advice? Choose the IB Psychology Level of Analysis that your teacher begins with. This will maximise the amount of time you can spend learning this section.

TOP TIP TWO

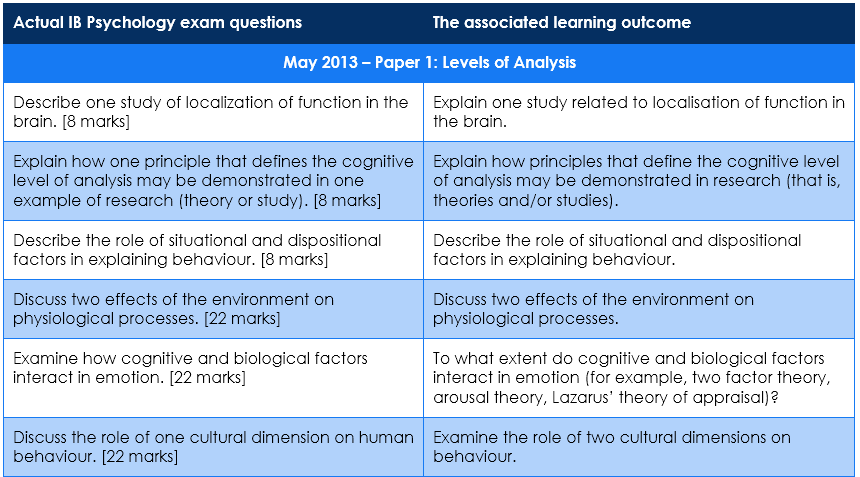

Prepare and memorise model answers to ALL of the extended response questions.

The extended response questions are the the IB Pychology examination essay questions - i.e., the big 22 mark answers. Prepare perfect 22 mark answers across one of the Levels of Analysis, and across each of the IB Psychology options (e.g., Abnormal and Human Relationships).

In each option you will need to answer a single question. So for HL you will need to answer two 22 mark questions, one from each option. IN SL, just one 22 mark question from the single IB Psychology option you have studied. Aim for maximum marks here. So that's 44/44 or 22/22.

TOP TIP THREE

Aim for maximum marks in your IB Psychology IA.

Essentially, any additional mark you gain in the internal assessment component of the course, is an additional total mark you can add to your final IB Psychology score. Start early. Put lots of effort in. Listen to your teacher. Ask your teacher to read over lots of sections before submitting the final draft. Get lots of feedback so your final draft is as good as most students' final submissions.

TOP TIP FOUR

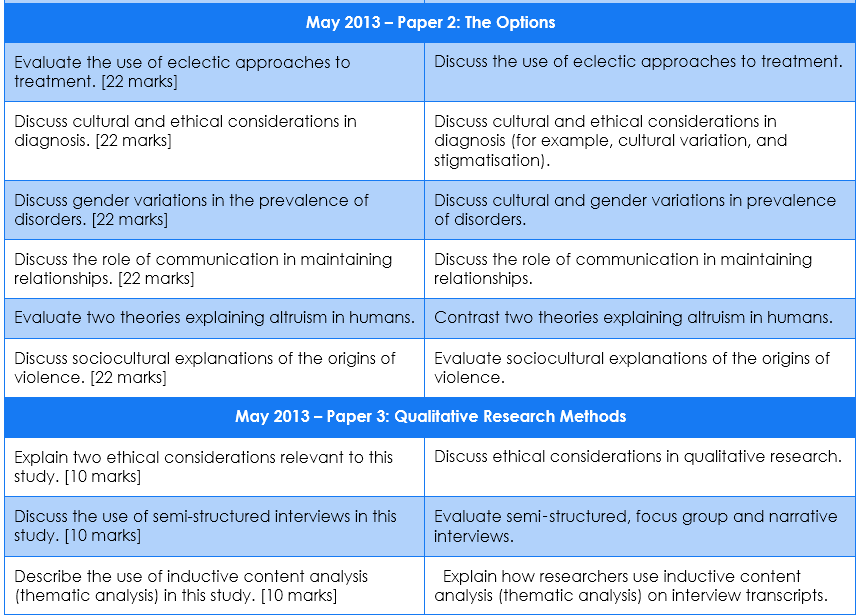

Do NOT ignore the Qualitative Research Methods component of the course, because your IB Psychology teacher almost certainly WILL!

It has long been identified that teachers neither spend enough time or go into this topic in enough depth. The majority of students do very poorly here, and as a result the grade boundaries in the HL Paper 3 examination are set incredibly low. Learn the content and learn to apply it to sample stimulus material.

TOP TIP FIVE

Forget about any of the short answer learning outcomes in the Options section of the IB Psychology course.

Examiners can twist exam questions to fit these, but they usually don't. There are always straightforward back-up questions to fall back on. Save your time for memorising your model answers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed